When confronted with a work of art, especially a work of visual art, I often find myself weaving the work into a story, one that involves an inevitable conflict between sense perception and abstraction. Here’s how I do it: I tell myself that, rather than speaking of and for itself, the work in question is instead a reply of sorts, taking its motivation from what Marxists since Lukács have called a “form-problem”—the work in other words a provisional “solution,” using the tools of a given medium, to the representational challenges posed by a unique and otherwise unrecognizable historical condition or dilemma. According to this schema, said condition or dilemma, regarded now as the true “content” of the work, can only become available to consciousness either through the work itself or through others of its kind.

Take the adjoining photograph, where I can be seen holding a two-song 7” record by Chicago-based post-hardcore band Shellac. Released by indie label Drag City on August 22, 1994, the record is already more than 20 years old—a vintage artifact from the final years of the last century.

Before continuing, I should admit here by way of introduction that I harbor a certain fondness for this object. I like it. It’s a favorite item of mine. I even feel compelled to share with you the fact that I remember the precise circumstances through which I acquired this record, as it was among a large and thus uncharacteristic purchase I made one afternoon toward the end of my freshman year, when Spectrum Records, a student-run music store on the campus of the school I attended, with little fanfare liquidated its entire inventory, everything in the store heavily discounted in ways that reminded me of Toys “R” Us shopping sprees I dreamed about as a child, these conditions somehow making the purchase easy to recall now in great detail.

While all of this should serve as a healthy reminder of the Shellac record’s status as a commodity, a thing made to be bought and sold, I can’t help also regarding it—the record’s packaging, first and foremost, but perhaps also the record as a whole—as a work of visual art, amenable to the mode of interpretation mentioned earlier.

By the way, feel free at this point to question my tendency to paint myself as compulsive in relation to this artifact. I, too, suspect that my attachment to the record, and to others as well, is at least partly fetishistic in character. What’s interesting, though, is that the objects I fetishize demand in most cases to be gratified in a very particular way, via hermeneutics rather than sex.

Thus, when I encounter a record in my collection like this Shellac one, part of me wants not so much to play the record, as to set to work trying to reinvent the object’s form-problem—an act of no small complexity, given that naming or even just describing a form-problem invites a form-problem of its own (there being no “neutral” way of speaking of such matters). Perhaps the best we can do in the face of these kinds of representational dilemmas is to switch between two or more codes or schemes in pursuit of a metalanguage, always keeping in mind that while no name is perfect or fully commensurate with its object, some are more accurate than others.

And yet in practice, at least in the stories I tell myself, form-problems always appear as questions, the work and its context thus resembling a short Socratic dialogue.

In the case of the Shellac record, if I were to try to pose its form-problem as a question, it might look a bit like the following:

How can a band communicate through product design and packaging—through use of visual language—a reluctance to participate in the commodification of culture? Using slightly different wording, I might also say: How can a band transform its labor into a commodity, while simultaneously expressing disdain for that process of commodification?

Satisfied with these initial formulations, I suppose I would then double back a few steps in order to explain how I got here. I should warn you, though, that whatever explanation I offer, it can only ever be a partial one at best, as an element of creative speculation enters unavoidably into this stage of the analysis.

Of course, most artists proceed without naming, without themselves being fully conscious of, and thus able to articulate, the form-problems they’re attempting to solve. Like those semen and saliva stains and other kinds of evidence that go undetected at crime scenes until viewed beneath UV forensic lamps, form-problems regularly fail to register at the level of discourse—unless, that is, one approaches them equipped, as mentioned before, with a critical vocabulary or the rudiments of a metalanguage. Hence the work of naming and describing tends to be performed after the fact by critics, the critic having to conduct a symptomatic reading, reconstructing the form-problem by way of its effects.

Let’s look again, then, at the object in our photograph.

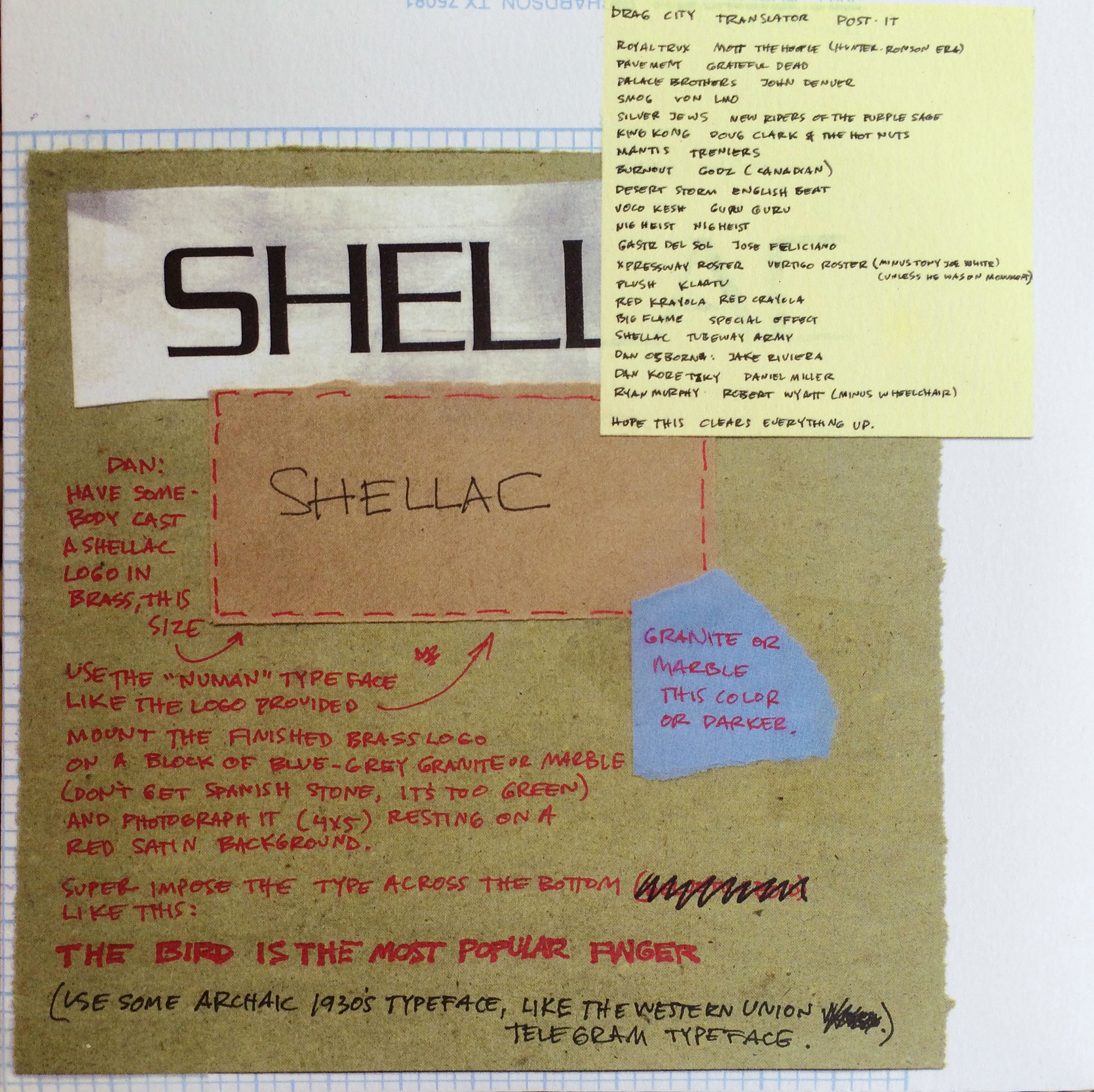

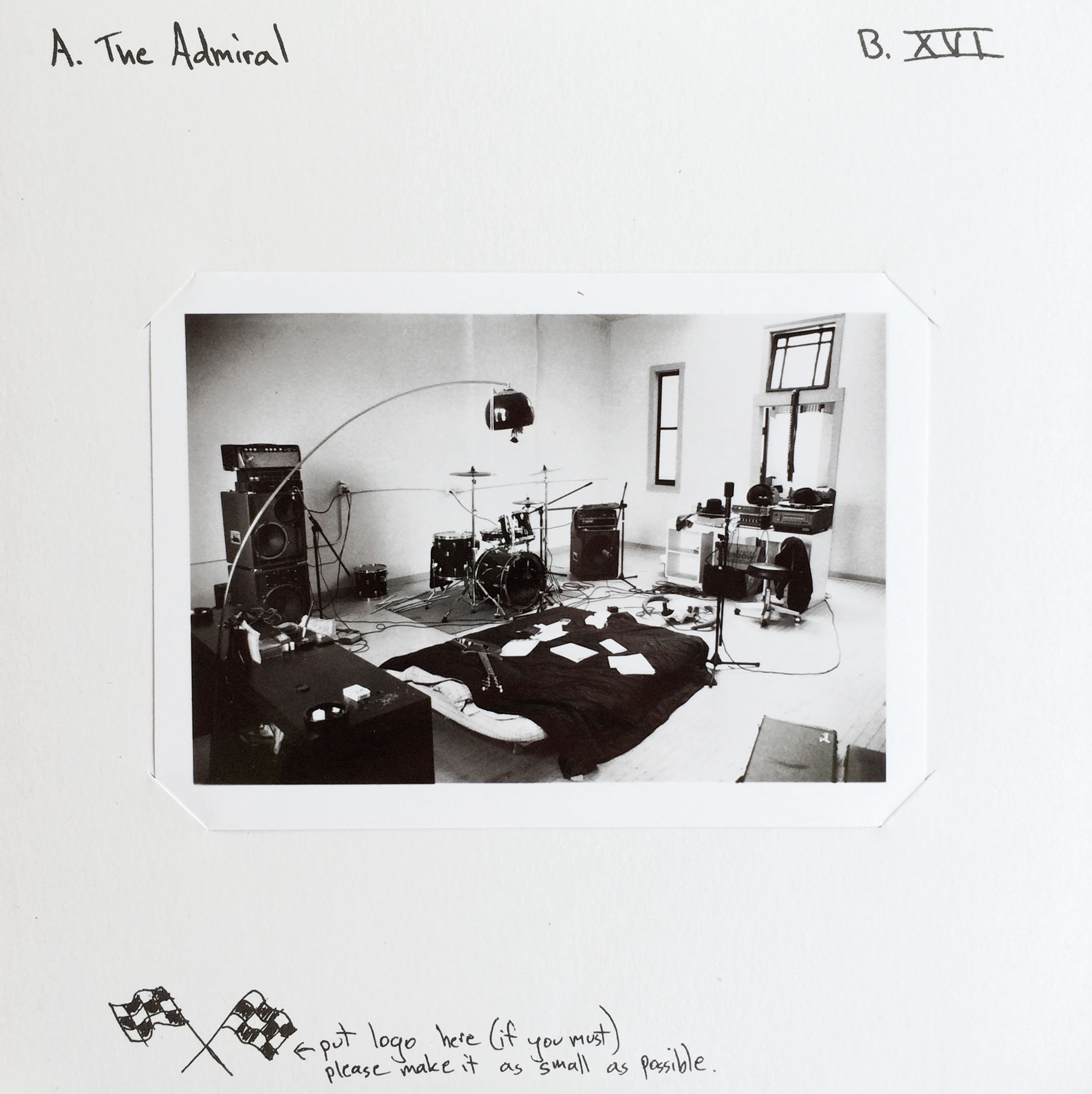

The Shellac record comes housed in a beige, textured cardstock sleeve. One side features a color reproduction of a mock-up containing band member Steve Albini’s detailed, handwritten instructions to Drag City label heads Dan Koretzky and Dan Osborn explaining the band’s wishes for how the sleeve should look. The reverse side of the sleeve, meanwhile, comes equipped with a removable B&W photograph, the corners of which have been tucked into small diagonals cut into the cardstock. The photo shows drummer Todd Trainer’s loft apartment, said apartment apparently having performed double duty during this period, serving not just as Trainer’s home at the time, but also as the band’s main practice and recording space. Indeed, the very songs featured on the record to which this photo is attached were themselves recorded in the space featured on the record’s sleeve.

Nearly everything about the work, in other words, seems to have been organized to provoke a response akin to Brecht’s famous Verfremdungseffekt, as the devices used to produce the record are at all points deliberately laid bare by the record itself.

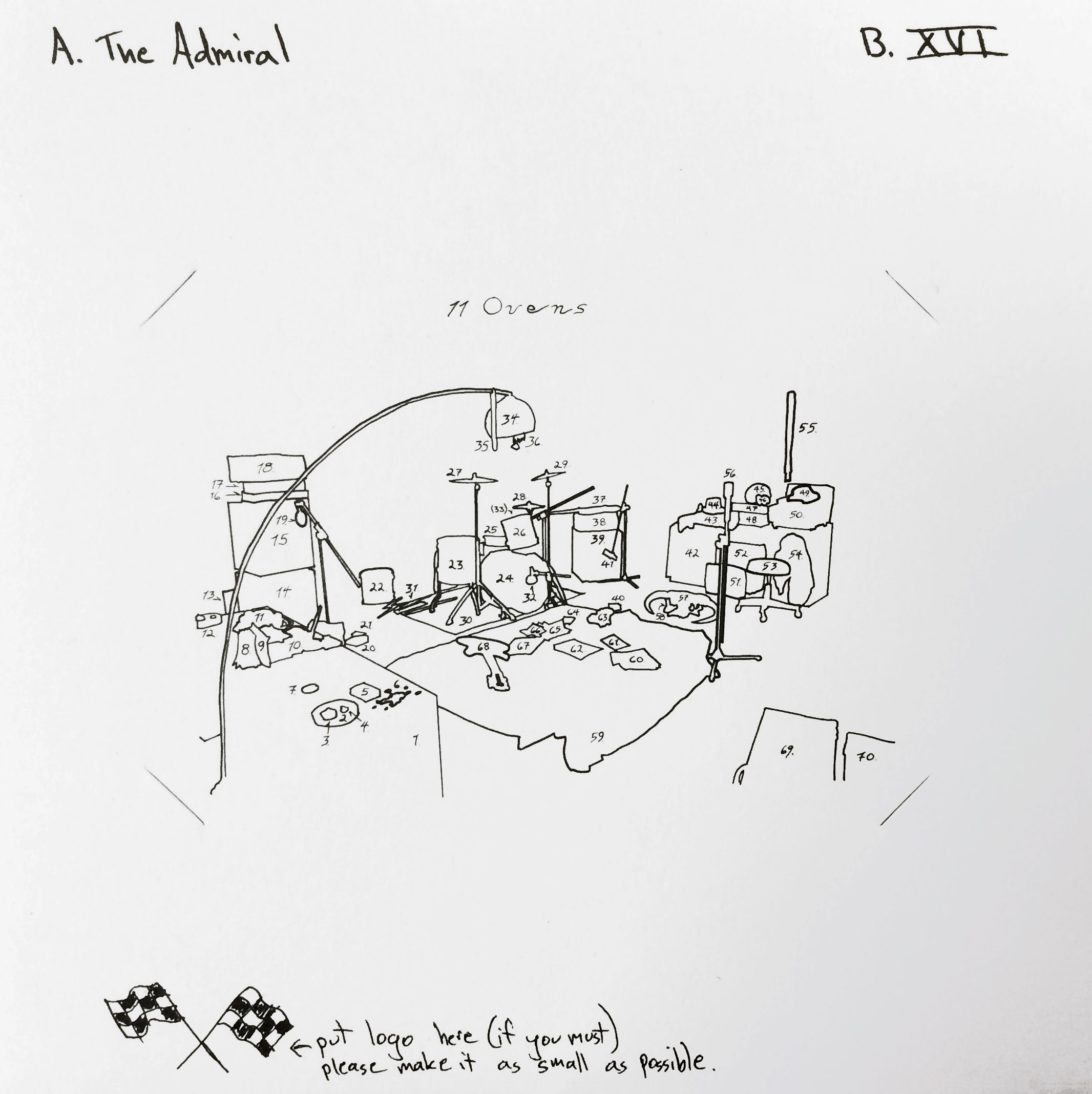

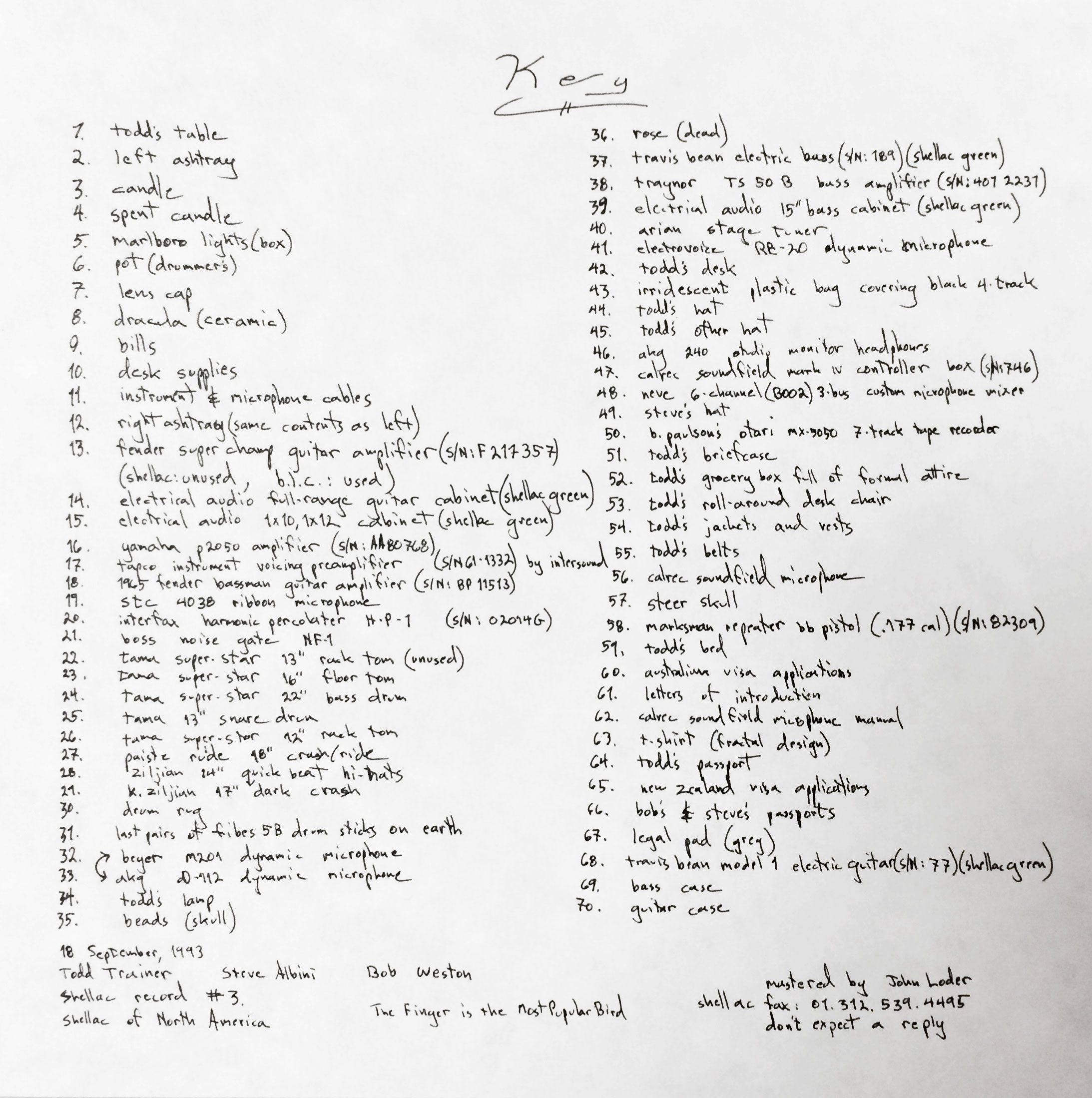

Nor does this initial description exhaust the record’s supply of documentation pertaining to the conditions of its making. When one lifts the aforementioned B&W print from the record’s sleeve, one finds beneath it a remarkable “paint-by-numbers”-style line drawing reproducing in outline form all of the items from the photograph, with each item—the drawing lists seventy—here assigned its own number. These numbers eventually acquire meaning as one explores the sleeve’s interior, for they appear again in list form on a paper insert included with the record, this insert serving as the photograph’s “key” or “legend,” and hence also as manifest of the contents of Trainer’s loft, naming as it does all of the items featured therein.

As far as I can tell, this mode of representation, used perhaps most famously to supplement the artwork for the Beatles album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, at present lacks an agreed-upon designation. In terms of genre, it’s a close cousin of paint by number kits and “exploded-view” diagrams, but with the basic form of each applied to a different task. When asked, though, several friends who work in graphic design noted also having heard such drawings referred to on occasion as “illustration keys” and “picture legends.”

Whatever its name, what’s remarkable about the drawing is its level of detail. Viewers examining the drawing’s key, for instance, might notice various boho tchotchkes and household goods: items like “Todd’s table” and “pot (drummer’s).” But what we find here in far greater supply are lists of instruments and recording devices, all of these reported in ways that make them sound highly technical, some items specified even by way of serial number, as in “Interfax Harmonic Percolator H-P-1 (S/N: 02014G)” or “Fender Super Champ Guitar Amplifier (S/N: F217357).” It’s an odd move, even for a group whose most famous member is a recording engineer—so odd, in fact, that one has to wonder: what would provoke a band to be so frank and forthcoming with info about the tools of its trade?

My argument in what follows is that this technique, whereby a constellation of photographs and other visual aids are used to create an elaborately self-reflexive kind of packaging, one where the exterior of a product reveals or “lays bare” that product’s means and conditions of production—this, I’ll be suggesting, is the Shellac record’s “solution” to the form-problem I mentioned earlier, one involving a desire to push back against conditions of compulsory commodification. To take the claim a step further, I’m also going to contend that this particular form-problem distills, or is itself the distillation of, the central problem facing inheritors of the countercultural or “hip left” legacy in the early 1990s, that problem being how to revolt, or more simply, how to live in the age of TINA.

To this day, whenever I come across references to the slogan “There Is No Alternative,” this latter having been former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s way of insisting throughout her tenure that economic liberalism was the only game in town, the part of me that excels at pattern recognition inevitably pictures the stylized B&W logo from No Alternative, an alt-rock compilation record released in October 1993, ten months prior to the release of the Shellac record. For listeners of a certain age, No Alternative was kind of a big deal. As the website Stereogum noted in a 2013 article commemorating the record’s twentieth anniversary, the comp was especially notable, and arguably remains so today, given the way “it captures the American alternative scene at its commercial, cultural, and critical peak.”

Of course, you may think I’m absurd for trying to force a connection between these widely disparate phenomena. The comp title’s replication of Thatcher’s slogan may indeed be a matter of pure coincidence, those who coined it quite possibly blissfully unaware of TINA, or the Fukuyama thesis, or any of the other emblems used today to evoke the immediate post-Cold War era’s apparent closure of political horizons. Fair enough. I concede that all of this is possible. Yet given my convictions regarding the role of something like a “political unconscious” in everyday life, I prefer to think otherwise.

I prefer to think, rather, that the word “alternative” came loaded with a certain subterranean political resonance in those days, so that when people began using the term to name a particularly noisy or angst-ridden strain of rock music, they were in fact expressing a secret wish—secret even unto them, perhaps—for spaces of difference, spaces offering even temporary release from the market pressures of a global capitalism that, for some of us, was just then beginning to feel less like “freedom” than like a planet-wide open-air prison.

This takes us to the point that I suppose I’ve been steering us toward all along, namely that certain iconic alternative rock records of the early 1990s, No Alternative and Shellac’s “The Bird Is The Most Popular Finger” included, are iconic precisely because of having been designed in accordance with desires or sentiments of the kind I’ve just described.

For those who remain skeptical, or who don’t yet share my convictions, allow me to add here my assurance to you that a wish can be organized in relation to an entity as abstract as “global capitalism” even when, as is usually the case, that total system has only ever been grasped by participants synecdochically, pars pro toto, as for instance via intermediate categories—euphemisms, basically—popular among indie rockers in the nineties, like “corporate rock,” “major labels,” or “the mainstream.”

To see what I mean, try recalling here that the Shellac record was released in late August 1994. Kurt Cobain, whose final album In Utero Shellac’s Steve Albini helped to produce, had committed suicide just a few months earlier, in April of that year. The suicide, as I’m sure most of you remember, was partly attributed to Cobain’s inability to cope with Nirvana’s rapid commercial success. For some of us, perhaps, that explanation seems flawed or simplistic now in hindsight. What’s important, though, is that it was taken for truth by most people at the time, for that alone raises the stakes of our form-problem considerably, alternative rock’s relationship to the process of commodification suddenly at that moment looking like it had generated casualties, and thus appearing to some as a matter of life and death.

This was a time, in other words, when it mattered whether or not a band signed to a major label. Loose, informal disputes among those operating in the spaces opened up by punk and its offshoots had by the early nineties hardened into full-formed schisms. Like the Utopians in Mary McCarthy’s 1949 novella The Oasis, the nineties alt-rock world possessed its so-called “Purist” and “Realist” camps. The Purists adhered to the rules of a DIY platform that explicitly forbade corporate affiliations, while the Realists bent those rules in one way or another, capitulating to industry demands in hopes of one day reaching a larger audience. “Alternative rock” itself became a suspect moniker as the decade progressed, with Purists writing the term off as a mere marketing construct foisted on Gen-Xers by the likes of Rolling Stone and MTV.

With the lifestyles that they’d cultivated more or less in secret over the last decade suddenly threatened by the prospect of co-optation, indie bands belonging to what I’ve been calling the Purist camp began to deploy techniques of self-sabotage, making their music deliberately “difficult” either by extending the abrasiveness of punk and hardcore (as is the case, for instance, with variants like grindcore and screamo), or by simply “mellowing out” and dabbling in unfashionable genres like folk and lounge. Lo-fi recordings full of amateurish playing and abstruse lyrics, with vocals either mumbled, screamed, or buried in the mix: these became signature features of indie music in the years just before and just after the turn of the millennium.

Formed in 1992 by veterans of the punk and hardcore scenes, Shellac pursued the first of these approaches. Often describing itself as a “minimalist rock trio,” the band builds its songs (across a body of work that now includes five studio albums) around just a few basic elements: the distinctive scrape and yowl of Albini’s guitars and vocals, paired with brutal, primitive drumming and obsessively repeated bass lines.

This austere, uncompromising musical equation exemplifies the values and contradictions of an indie milieu invested in ritualized performances of authenticity.

As with Purists in other genres, indie Purists routinely assert a sense of their collective self-identity by staging emotionally-charged debates about what counts as genuinely or authentically DIY behavior—a process that quite naturally requires as its corollary the condemnation of some evil, inauthentic “Other.” I’m tempted to say that this fake, ersatz other is simply “mass culture,” the entire indie project thus founded upon, or beginning from some fundamental agreement with, those Left critiques of American mass culture formulated by groups like the Frankfurt School and popularized here in the US in the pages of journals like Partisan Review. For now, though, let’s just insist that indie’s emphasis on authenticity be understood as a kind of talisman used to ward off the threat of co-optation.

Amidst this threat, never more real than at the height of the post-Nevermind major label feeding frenzy, it appeared as though one couldn’t rest content with simply being authentic or inhabiting one’s authenticity in a purely spontaneous or unselfconscious manner—for in order for this authenticity to contribute to the preservation of a community of authentically anti-corporate individuals, a community whose members actually lived in accordance with their self-professed ideals, one would have to somehow demonstrate one’s intentions by performing or displaying these for a public.

And yet, clearly it wasn’t enough to just release one’s records on an independent label. After all, there was no guarantee that one wouldn’t sell out by the time of one’s next release.

And so, of course, the responsibility fell on art itself to act as the site for these demonstrations, the community distinguishing its friends from its enemies on the basis of particular kinds of sounds and images and recording practices, as if the bad faith of an inauthentic artist would inexorably give rise to bad art.

Albini himself suggested as much, perhaps most memorably in “The Problem With Music,” an article he published in a Chicago-based zine called The Baffler in 1992. Artists that sign with major labels tend to make bad records, he argued, not just because of their incompetence, and not just because of their careerist impulses, but because of detrimental but nevertheless standard practices of the record industry—practices that range anywhere from the use of dubious contracts to recording techniques that “make everything sound like a beer commercial.”

These Purist assumptions about some reliable link between bad faith and bad music are troubled, however, by what Saussure described as the famously “arbitrary” or “unmotivated” relationship between signifiers and signifieds. There’s nothing inherently antithetical to capitalism, for example, in the way one plays one’s guitar.

What’s interesting about “The Bird Is The Most Popular Finger,” however, is that instead of just attempting to meet these challenges musically, it also addresses them at the level of artwork and sleeve design, and in so doing, develops a temporary solution to the form-problem mentioned above.

What we have with this record, in other words, is a commodity that, by way of its packaging, performs an autocritique of its status as a commodity.

A more cynical way of saying the same thing is that, at every point in the design of the record, the band promotes itself to future consumers by indicating its ambivalence about self-promotion—ambivalence, too, I imagine, about the entire process whereby, in order to make a living, one is forced to insert oneself into the exchange relation and bring one’s labor to market, one’s music reduced to a thing to be packaged, that packaging, given its placement in said system of exchange, by its nature functioning as a form of advertising.

I see evidence of this ambivalence, for instance, along the bottom edge of the side of the record featuring the B&W photograph, whereon there appears a drawing of the iconic Drag City checkered racing flags, with a handwritten message beside it reading, “put logo here (if you must) / please make it as small as possible.” The band communicates a similar sentiment on the label of the record’s B-side, where Albini has written another note to the people at Drag City, this time stating, in a more humorous register, “Dan—Do NOT put your shitty logo on the label!”

The Marxist in me is eager to read all of this, finally, as a critique of commodity fetishism, recast visually in terms relevant to the life experiences of a rock band.

After all, one doesn’t detect an inwardly-directed sense of shame, or some sort of guilty conscience, motivating the act of autocritique performed by the inclusion of such statements in the record’s packaging. Shellac never really partook of grunge’s theatrics of self-loathing, a trend instantiated, for instance, in popular songs of the alt-rock era like Beck’s “Loser,” Radiohead’s “Creep,” and Mudhoney’s “Touch Me I’m Sick.” Shellac’s critique, rather, is clearly pointed outward, taking as its target a process of commodification that breeds ignorance about conditions of production.

When asked by Daniel Brockman of The Boston Phoenix about whether Shellac “set out in an unspoken way to not participate in a capitalistic band system,” Albini responded by stating, “The way that we would probably describe it is that we want to keep all of our relationships on the personal and human level: every single one of them. The relationship with the audience should be a normal regular human interaction, it shouldn’t be primarily a business transaction. […]. For us, that’s the way we want to conduct ourselves. It’s not necessarily that it’s anti-capitalist, although it works out that way…and I’m fine with it.” Discovering this transcript in the course of my research for this essay, I couldn’t help but feel an immediate sense of excitement, as it seems to lend credence to the story I’ve been telling. What Albini fails to mention, though, is that commodity fetishism is the key problem likely to complicate this code of conduct—for as soon as a band takes its music out of the sphere of live performance and converts it into a marketable object, the potential emerges for the audience’s relationship to the band to be replaced by a relationship to a thing, with the songwriting and the recording and all of the other human labor that goes into the making of that thing effaced by the finished product.

Hence the form-problem with which we began. In order for the band to receive compensation for its artistic labor, it had to convert that labor into a commodity. At the same time, in order to remain true to the intentions of the larger indie community, it also needed to communicate its disdain for this process of commodification. To meet these conditions of its form-problem, then, the band adopted a rather ingenious strategy: it turned the packaging of its record into a form of documentation displaying traces of the DIY labor practices used in the record’s making, thus exposing that which the commodity-form otherwise tends to hide.

To testify to the “authenticity” of these various traces, the record makes sure to employ particular devices like handwriting, photography, and semi-live audio recordings: signs, in other words, that bear what nineteenth-century philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce called an “indexical” relationship to the referent-world, or the world of human labor. (Whether made of vinyl or shellac, of course, records, too, bear an indexical relationship to the music they’re used to convey.)

To conclude, then, perhaps we should ask ourselves: How successful is this strategy?

As a way of instantiating the authenticity of the band’s commitment to anti-corporate DIY principles, I’d say it’s pretty impeccable. And among codes of conduct stipulating how to live ethically as a leftist at a time when opportunities for more direct confrontations with capitalism appear foreclosed, DIY is probably as good a contender as any. In my first encounters with it amidst a mid-nineties hardcore scene where peers of mine were forming bands and putting on local all-ages shows in basements and VFW halls, DIY struck me with all the force of a holy decree, “Thou Shalt Do It Yourself,” its radical implications immediately apparent, I thought, given the way it emboldened ordinary people, people like my friends and I, to reclaim control over aspects of everyday life. But because the command also interpellates its addressees as individuals, DIY has always entertained conflicting political valences, finding advocates equally as much among “be-your-own-boss” capitalists as among “be-the-change-you-wish-to-see” anarchists and “workers’-control”-style communists. And since the action it compels never quite scales up beyond the level of small groups of individuals exchanging goods and services, none of the cultures produced by the DIY imperative are ever likely to deliver some long-sought-after antidote to commodity fetishism—nor, in all honesty, is culture really the appropriate place to look for such an antidote.

The Shellac record succeeds in laying bare some of the conditions that were involved in its production, but it’s not like this gesture lets the record off the hook, or exhausts its ability to deceive us. After all, we’re still only ever seeing a part of the total labor process: the part involving the band members themselves. Other parts of the commodity chain continue to elude our grasp.

Laying bare the device is only valuable, then, in that it enables the band to exert more control over, and take fuller credit for, a wider range of aspects of the record’s production. Albini’s hand, we learn, was literally all over the design of this record, as if he were simply terrified of outside interference. I can almost picture him now, wide-eyed, shouting, “If the Man gets his hands on our art, he’ll turn it into kitsch; therefore, we must Do It Ourselves”—DIY reduced here to a mere quality control procedure. It’s an unflattering portrait, to be sure, and one I’m loathe to endorse: a portrait not so much of rebellion against capitalism, but of the artist as control freak or the artist as micromanager.

It would seem, then, that the utopian ideal implied by the record is one involving a practice of transparency that makes possible, at best, something like an ethical form of consumption.

Many of us today are of course suspicious of such a project. We tell ourselves we know better than to expect our consumer goods to embody the kinds of virtues that capitalism makes it impossible for us to possess ourselves. Say the Shellac record had done exactly what I thought I wanted it to do. Say, in other words, it had projected an adamantly and robustly anti-capitalist ideology, back when I bought it as a teenager. What exactly would that have accomplished? Wouldn’t it have just allowed me to consume guiltlessly, my conscience at ease, fooled into thinking that the record had bestowed on me a kind of impunity?

The utopian in me prefers a more generous reading. I’m reminded here of a passage I came across in an essay by Perry Anderson. “Transparency,” says Anderson, “is one of the crucial defining characteristics of socialism: a community in which all the multiple mediations between our public and private existence are visible, where each social event can be seen right back to its source, and legible human intentions read everywhere on the face of the world.” Call me crazy, but for all my hesitations, in the end I suppose I see transparency of this sort as the latent ideal animating the aesthetic of the Shellac record. And for me, at least, any object that provokes us to imagine a world finally made legible is itself a thing worth heeding.