When is a black box not a black box? When it’s ajar.

Perform a Google Search on “Lycanthropocene” and the results are impressively few. So meager, in fact, that Google will offer you a syllabic dissection of the search term in hopes of leading you into more linguistically lucrative directions. Appealing to advertisers more eager to bid on keywords associated with a wireless service provider or a geological epoch distinguished by human disturbance writ large, Google politely asks “Did you mean lyca anthropocene?” Should you continue with the curious neologism anyways, the predictive analytics of the search engine will dutifully writhe, shape shifting to index this new term for future bidding wars.

With audacious insistence on using the term "Lycanthropocene," a Google Image search will yield approximately two results. There is an image of a classic wolfman, silhouetted against the moon with eyes glowing red, and an image of letters. These letters are sequenced so as to form words, and the words are arranged as lists which outline the keyword niche of the literary werewolf. This is a blip on the radar.

Eighty-two percent of attention goes to eight percent of the photos circulating on social networks. The 92% seldom receive views and yet burn as much energy as that which has gone viral. Social networking behemoths have taken to putting these pixels out to pasture, depositing them in low energy data farms. Such images can be retrieved, but not with the immediacy of the viral sort, thus calling into question the wisdom of taking a picture because it lasts longer.

Learned machines, we’ve been told, sort out the biggest of data, perform feats of organization, feats of visualization and feats of prediction which merit our praise and wonder. In the 1950s, Paint-by-Number kits offered post-war publics an opportunity to mimic the logic of automation, to actuate an image step-by-step, to think like a machine. ''Actors act in plays written by somebody else” notes Dan Robbins, co-inventor of the Paint-by-Number kits.

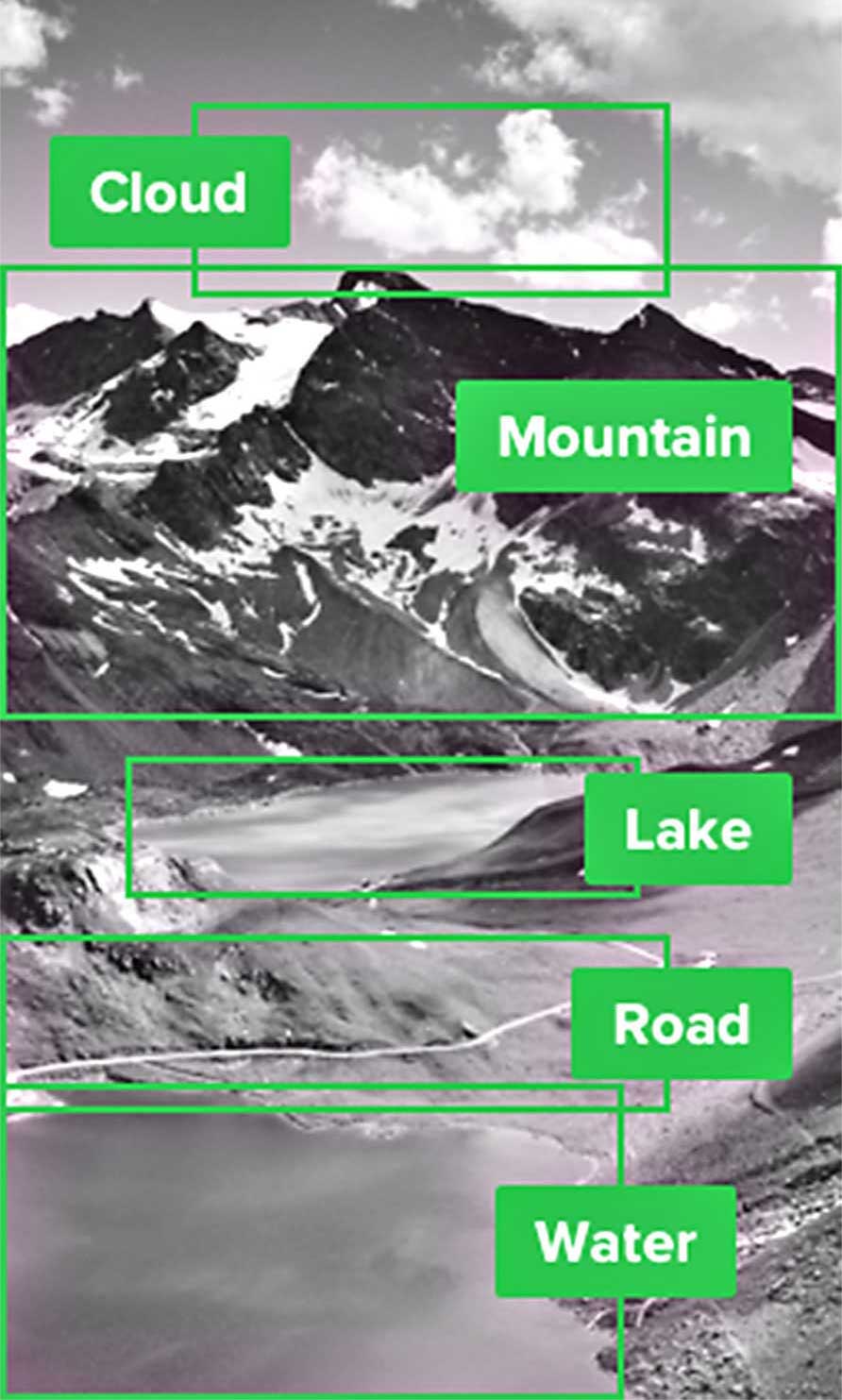

Imagine a dramatic production in which an old-school cabbie assumes the role of a self-driving car. In the first act, our hero navigates the density and heterogeneity of the city, demonstrating prodigious knowledge. In the second act we learn that even this most accomplished A.I. begins to panic when faced with endless amounts of data which it must consume and synthesize. Entertaining whimsy in its ways of seeing the world, the car pauses to admire a picturesque landscape, then issues an anticlimactic soliloquy: cloud, mountain, lake, road, water. A “quaint-ification” of the world is offered as a cathartic denouement in a play written by someone else.

Moving image feeds of city streets are meticulously labeled, often one frame at a time, over many hours of toil and attention. Thousands of human laborers working remotely and behind the scenes produce an explicit database of topographical knowledge to be performed auto-magically by sufficiently advanced technologies. For the self-driving car companies, the sheer volume of annotation required nixes anything but the most banal lexical units to be dispensed by the legions of outsourced clickworkers.

“If a system for thinking doesn’t make thinking simpler—allowing you to see farther and more deeply—it is useless,” asserts Theodor H. Nelson in Computer Lib / Dream Machines, his 1974 treatise on computer assisted learning. The map is not the terrain and, in the myriad cultural contexts of the world’s roadways, the terrain itself is not mappable with the precision of painting by number. What is a self-driving car’s tolerance for noise? Could an art car go stealth, mistaken by machine vision as a non-car, post-car, anti-car? What does artificial intelligence do with Ant Farm’s Cadillac Ranch?

“There are a screen and two throttles,” notes Nelson, evoking a vehicle while describing the interface for a form of hypertext he first devised in 1967. Nelson’s so-called “Stretch Text” permits the reader of a digital text to both “shrink” a wordy passage into a more concise statement, and to “stretch” a synopsis into detailed prose, populating the sequence with additional words with the ease of switching gears. Costly constraints on letters and word counts inspired senders of telegrams and later text messages to devise ingenious compressions, too, shrinking texts and spawning that tactical typo, the emoticon. The French workshop for potential literature, or Oulipo, might claim or defend anticipatory plagiary of Stretch Text in the form of “definitional literature,” a means of adding complexity to a string of text by replacing each noun with its dictionary definition.

A mountain was once considered sublime, inspiring a sense of awe in those who encountered it. Imaged, annotated and augmented with a vast amount of data over time, the resulting cultural cache evokes another sort of breathtaking mass to which a bevy of analytic tools may be deployed.

Perform a Google Image Search on “Big Data” and enjoy an influx of redundant repetitions of the search query, spelling out, verbatim, “Big Data.” Obsessive compulsive googling cannot much muster an explanatory image beyond this. There are clusters of personal electronics rendered as desktop icons and grouped in cloud-formation. There are anemic echoes of the planet, implied planets rendered as glowing wire-frames, implied planets comprised of points and paths, and hollowed earths devoid of hardware leaching into the soil.

Recognition of the Anthropocene, the proposed term for the present geological epoch, during which humanity has begun to profoundly alter the planetary systems of Earth, has been trailed by massive machine readable data sets measuring its characteristics. Contending with the cataclysmic and multi-faceted complexities of this geological turn, the processing of vast and heterogeneous quantities of anthropogenic impact data has been an illuminating resource for the scientific community. While former editor-in-chief of Wired magazine Chris Anderson once proclaimed that “With enough data, the numbers will speak for themselves,” positioning Big Data as an apparent cure-all for the ails of partial knowledge, the efficacy of these facts amongst non-experts has varied. From the abstraction posed by the concept of deep time, and the sheer scale of transformation already rendered upon the planet, actionable gestures to be carried out by an individual can be difficult to comprehend.

Perform a Google Image Search on “Anthropocene.” The results are picturesque. As Wolfgang Lucht and Philipp Oswalt similarly demonstrate in their seminar Imaging the Anthropocene, this query tends to produce an interchangeable deluge of planetary portraiture caricaturing the collective anthropocenster’s sin, but with little nuance or novelty with which to apprehend the truly wicked problems under canvas. Lucht and Oswalt use this computational conceit to frame a history of existing images of the Earth and the Anthropocene, and remind their audience that “each consumer is co-producing the Anthropocene by consuming, and that consumption is a matter of design.”

Complicating this consumer critique are the material consequences of assessing images of the Anthropocene online, as artist Joana Moll demonstrates with CO2GLE, an installation tracking the emissions produced by Google in real-time.

According to Google’s own calculations, circa 2009, every thousand search queries is equivalent to the CO2 pollution produced in a half-mile travelled by a gas guzzling automobile. The Google website itself, due to its vastness and frequent use, averages 1000 lbs. of carbon dioxide emission every second.

Gasp at these figures but don’t hold your breath. You will find it hard to resist performing a Google Image Search on “1000 lbs” to rally an aspiring Atlas: muscled bodies hoisting impossible weight, piles of narcotics, adepts at obesity, and assorted carts and scaffolding manufactured and exported from the Qingdao Free Trade Zone. Atlas personifies endurance and astronomy, database and algorithm, a mountain and a collection of maps and measurements thereof.

Of the perceived objectivity and unquestioned authority of algorithms, media scholar Tarleton Gillespie likens the appeal of these procedures to the trust previously held by “credentialed experts, the scientific method, common sense, or the word of God.” Drawing comparison with these sites of knowledge production and certification, Gillespie emphasizes social practice and institutional policy as the fundamental scaffolding in the algorithmic regulation of relevant knowledge. Earlier models of measurement and classification, including Carl Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae (1735), The Dewey Decimal System (1876), and Cesare Lombroso’s Criminal Man (1911) have revealed inherent biases when scrutinized, and Gillespie likewise recommends critical attention be paid to the patterns of inclusion, criteria for relevance and other “palpable but opaque undercurrents that move quietly beneath knowledge when it is managed by algorithms.” Because savvy charlatans and accomplished magi have also been invested in knowledge management through the ages, it is not inconceivable that there are other practices, egregious and adroit, that mentor today’s algorithmic adjudicators.

Networked cultures of the late 19th century included large-scale circuses travelling by railroad, with temporary tent cities arranged at each locale so as to direct traffic past a variety of enticing attractions. Known as the “midway” for its location in-between the entrance and the big top, this procession of rides, games, concessions and sideshow exhibits soon splintered off into an autonomous entertainment enterprise.

Like the endless scroll of a Facebook feed, the carnival midway was envisioned as a continuous spectacle, an experience architecturally designed as perpetual. Once you entered, it was difficult to figure out how to leave–and furthermore, there were spirited barkers vying for your attention, garish banners boasting exciting feats and freaks of nature, offset echoes of click-bait designed to capture your pay of attention and dollars.

Cribbing notes from these carnival colleagues, the patent-medicine retailer Rexall marketed the “Americanitis Elixir” in 1903, claiming their noxious brew of chloroform and alcohol would alleviate the burdens of the eponymous disease. So oddly American seemed the variety of nervous disorders to a German doctor visiting the country in the 1880s, that he invented the term “Americanitis,” down-throttling a wealth of wordy denunciations of industrialization and urbanization into a memorable neologism. By the 1890s, “Americanitis” had gone viral, popping up in medical journals, reviews, advice columns and the marketing schemes of Rexall.

Along with their attention to linguistic capital, Rexall performed a cunning misdirection or “interpolation of non-essentials,” as magician Nevil Maskelyne writes in Our Magic, published in 1911. For misdirection to be successful, one must invent “matters which occupy the attention of the audience,” the author explains, “to the exclusion of essential details in procedure or construction.” Maskelyne mischievously demonstrated this principle several years earlier in a pointed critique of Guglielmo Marconi’s claim to have devised a private and secure means of wireless telegraphy. With crowds gathered in London to witness Marconi’s demonstration, “[the] machinery began to tap out a message, but it didn’t belong to the Italian scientist” as writer Thomas McMullan describes. Maskelyne diverted attention away from Marconi’s claims by inserting his own non-essential Morse code missives: “Rats rats rats rats,” and then “There was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quite prettily.”

Whether the magician was acting on behalf of a rival company or carrying out a personal grudge, has been debated. Telegraphy played covert accomplice to Maskelyne’s mind-control illusions on stage, a context where feats of astonishment are framed as an opportunity for the attentive viewer to teach themselves scientific principles. Supernatural associations were shed by most magicians during the Enlightenment, in favor of a passive-aggressive form of pedagogy whereby explanation of a subject is occluded from direct view. Positioned in the role of the sleuth, as Colin Williamson suggests, the engaged spectator at a magic show turned a perplexing illusion into an auto-didactic occasion, endeavoring to comprehend the hidden systems more deeply. For Maskelyne, trolling Marconi was an opportunity to render an object lesson in the limits of hubristic promotion, perpetrating a denial of service attack as a means of provoking discussion about data security.

Perhaps the initial jolt for the crowds gathered in London was the realization that Maskelyne did not make use of sanctioned keywords in his messaging. Encoding was customary for correspondents seeking economy and security in telegraphic exchanges, with linguistic patterns consolidated, categorized and authorized in the approximating phrases of guarded codebooks.

“By using certain phrases and not others“ as N. Katherine Hayles describes, “[codebooks] not only disciplined language used but also subtly guided it along paths the compilers deemed efficacious.” If this authoritarian creep was mitigated temporarily by emerging models of telecommunication, it has returned under the auspices of the search query. Google’s autocomplete algorithms function as a type of “linguistic prosthesis,” Frederic Kaplan argues, “[tending] to transform natural language into more regular, economically exploitable linguistic subsets” based on input data that Google’s system itself shepherds. As this algorithmically mediated linguistic capitalism expands, misspelled words may be eliminated in favor of statistically viable alternatives and, in turn, shadow economies of expression will thrive. Considering the derelict status of typos, critically-minded conjurors may continue to cast spells as a form of linguistic misdirection. Incantations of note include those from clever netizens who have scooped up bargains on online auction sites. In this scenario, pennies are paid for “dinner tables,” and other appropriately pricey objects that have been left languishing in ill-attended posts because they were accidentally mislabeled as “diner tables.” Lexiconspiracy, a self-reflexive example of a magical spell[ing], is premised on recombining words syllabically. This sort of neologistic practice may provide “security through obscurity” to the extent that it is used only within a limited pool of network-enabled participants, or enact its own idiosyncratic form of linguistic enclosure, over time. In 2007, artists Linda Hilfling and Erik Borra demonstrated that the filtering system of Google China could be evaded with deliberate typos on terms like “Tiananmen Square,” revealing censored information through a matrix of misspelling.

The curtains open onto a machine readable array of clouds, mountains, lakes, roads and water:

A: What's that over there on the radar?

B: Oh, that's the Lycanthropocene.

A: What's the Lycanthropocene?

B: Oh, it’s the present geological epoch during which humanity has begun to have a significant impact on the environment.

A: That’s the Anthropocene.

B: Well then, that's no Lycanthropocene!

Perform a Google Image Search on “cloud” and the results, like the modern meaning, seem “suspended in the sky.” In Old English, the word cloud meant “masses of rock” and today the inherent weight of information infrastructure keeping “the cloud” aloft is evaporated into a visual chorus of cumulus clouds. Etymologically there is a link to “accumulation,” but cumulus clouds will be remembered as idyllic. The fluffy, puffy sort on which angelic cartoon characters might cavort, where gods of yore lazed about, and in which we are compelled to seek out shapes, get lost, or confirm that it looks like it’s going to be a nice day.