The Postmodern Economy of Mistrust

Part 1: Blockchain and the Postmodern Design

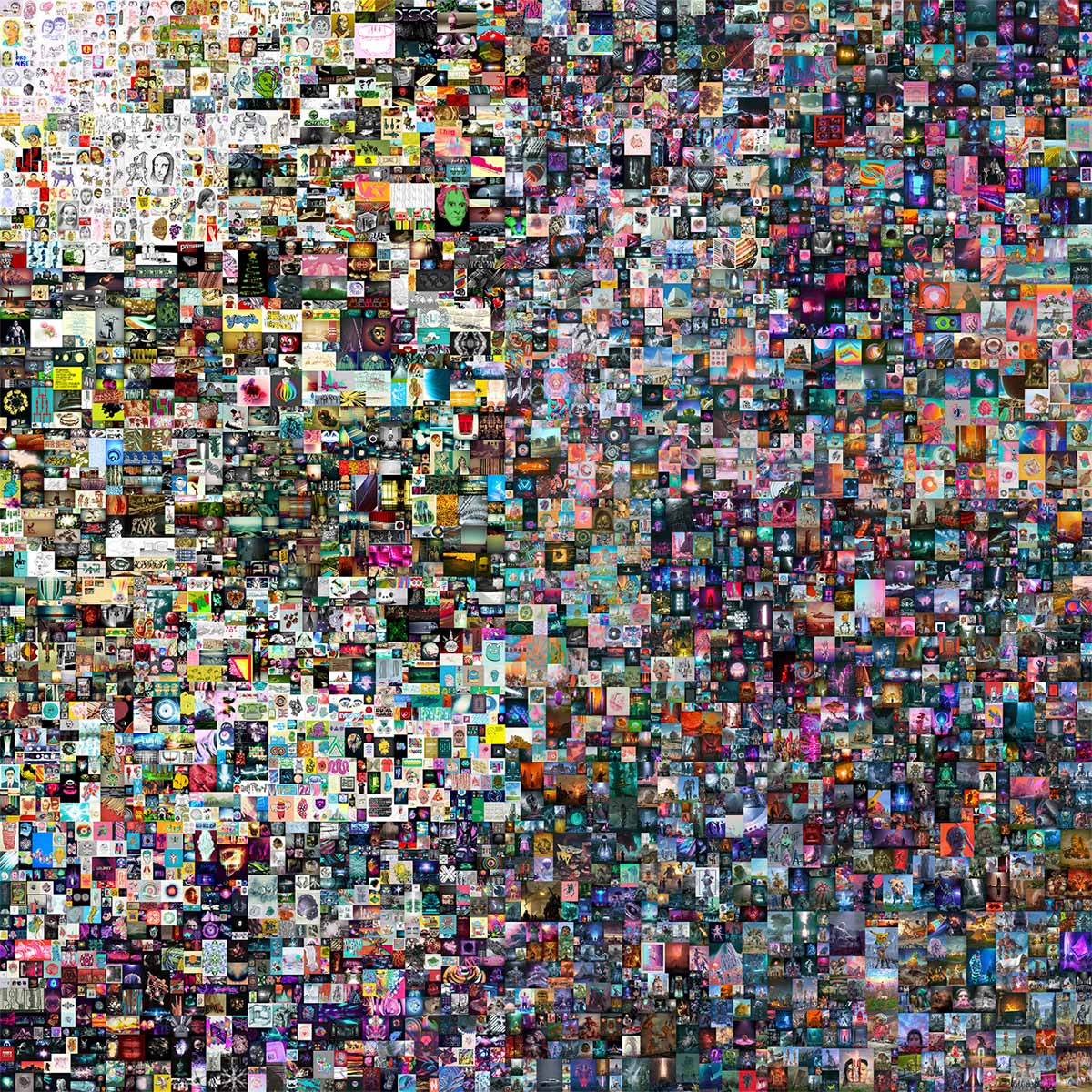

It is in the shadow of its price tag that Beeple’s EVERYDAYS: The First 5000 Days spent the aftermath of its historic sale at the Christie’s auction house. The news, as it was initially reported, read as an outlandish extravagance: an institutional giant of the artworld establishment facilitates the sale of a single jpeg file to an anonymous buyer for an astonishing $69 million worth of Ether cryptocurrency. When it came to the underlying crypto and Blockchain technology that tokenized the jpeg as unique and authentic, making the transaction possible, the general suspicion that often accompanies novelty grew in proportions, as the sale seemed to touch upon spheres of influence far exceeding that of the art world alone. EVERYDAYS provoked a surge of interest in crypto and Blockchain technology and resulted in reactions ranging from overzealous embrace to hysterical rejection. As an art-market phenomenon, The First 5000 Days felt like the beginning of some radically new era. Its polarizing effect, in some part, stemmed from crypto's claim to validity that relies mainly on its challenging of the national currencies, thus threatening not only central banks but also national governments. The sale's new format certainly struck a nerve at a time of increasing anxiety as our historical moment was informed by the still-raging COVID pandemic and its disastrous economic consequences for the majority of the world population, coupled with political turmoil unraveling across the globe, perpetuating discourses of post-truth, alternative facts, and the proliferation of conspiracy theories. The work itself, like many NFT artworks today, was seen largely as a collectible item, secondary in importance to the technology that made its acquisition possible.

Yet situating EVERYDAYS art historically may provide a contextual and formal understanding of the fiscal development we are witnessing. To better appreciate the work’s aesthetic qualities and art historical lineage, this two-part text invites the reader to follow a bifurcating line of inquiry. The first part of the essay outlines the structural relationship between the Blockchain infrastructure that underpins EVERYDAYS echoing in its aesthetic, and the formal specificities of the postmodern architecture exemplified by the 1970’s Bonaventure hotel, as described by the American theoretician and literary critic Fredric Jameson. The second part focuses on The First 5000 Days in the context of the emergence of cryptocurrency as a doubt-riddled alternative to fiat currencies. I place this work in conversation with the centuries-old art practice of paper trompe l’oeil, which at times spoke to an equivalent skepticism towards paper as a new monetary medium in 18th-century Europe as the world of finance grew increasingly immaterial and mobile. These seemingly unlikely pairings accentuate ruptures and unveil continuities between the contemporary moment and two different but, I hope to show, not wholly unrelated historical periods: the cementing of postmodern consumer capitalism and the emergence of the modern paper economy.

As a whole, this essay approaches Beeple’s EVERYDAYS in relation to artistic practices that engage matters of trick and risk at the time of mutating economic systems. The notion of trust is a useful guiding category for appreciating the stakes of these artworks, as The First 5000 Days raises questions about the way trust figures in new digital art and the Blockchain economy. Crypto’s surging prominence hinges on the infrastructural proposition to fork away from the modern fiat economy, which, much like modernity itself, relies on trust-backed social contracts, and toward a postmodern economy that replaces social trust with technological advancement and the computing consensus—"in code we trust." So, the artwork’s embeddedness in the context of cryptocurrency initially set up EVERYDAYS as an integral part in the process of acculturating the public to a low-trust economy. While the infrastructural aspect of this development has been pondered ad nauseam, the examinations of its aesthetic component remain to be explored. Approaching The First 5000 Days alongside postmodern architecture and paper trompe l’oeil, artistic utterances informed formally by market logic, allows to better investigate the ever-complex relationships between aesthetic and economic forms.

I.

A graphic designer by trade, Mike Winkelmann (aka Beeple), began making an image daily and posting it on social media sometime around 2007. As the title suggests, EVERYDAYS constitutes the first 5,000 images of said exercise and amounts to a digital “opus,” an archive of vivid, humorous, and terrifying visuals. Christie’s website presents the work as a pixel-like square of images arranged in a “loose chronological order,” containing a dizzying amount of visual information. If the financial infrastructure underpinning EVERYDAYS as an event makes it difficult to see it as artwork, the digital presentation of the work makes it difficult to look—the human eye has no place to rest in Beeple’s shimmering plethora. An eager viewer can navigate the work by zooming in on different parts of the assemblage and see Winkelmann perfecting his craft and finding his voice. The visuals in the upper left corner present simple line drawings and portraits of human figures. As the images gradually cascade down into the lower right, they morph into hyper-digital dystopian landscapes and alternative realities. It is in his later works that Beeple develops his signature tone, lampooning the political media landscape, re-imagining, among other things, US negotiations with North Korea, the vice-presidency of Mike Pence, the January 6th insurrection, etc.

Despite the seemingly specific references to political and cultural figures and events, EVERYDAYS establishes a peculiar time-space of segmented temporality, featuring a subjectively picked-out sequence of satirized events. As we see a cherubic Trump grinding on the Capitol building, or Michael Jackson’s and Kim Jong-un’s skulls melding into a single gigantic head amidst an idyllic meadow, we navigate a gaudy matrix of information that refuses to privilege one event over the next. EVERYDAYS presents itself as a digital sponge that absorbs the news media and regurgitates the information in a grotesque, sardonic fever dream. The seeming limitlessness of visual material exacerbates something modernists termed an “allover” composition, which, in the context of un-delineated digital space, can truly spread everywhere. And while caricatures of popular figures undeniably associate The First 5000 Days with historically- and culturally-specific events, the overall arrangement of the images speaks to a broader contemporaneous moment that at times feels to be saturated with uncertainty and eerie emptiness among the boundless over-production.

The understanding of Blockchain as a distinctively postmodern technology has been addressed in varying detail by pioneers of crypto art. What can be detected in Beeple’s work formally and observed in the crypto market on the level of infrastructure, is also embedded in the Blockchain on the programming level. Rhea Myers (then writing under the name Rob Myers), one of the first NFT artists and theoreticians, points out that Blockchain computing “departs from the assumptions of security and consistency that were foundational to computing models developed through the twentieth century” and facilitates a duplication of “existing market-currency models without the need for centralized banks or state operations.” Notions of “security and consistency” (foundational for the emergence of trust) are replaced with radical transparency and the anonymity of peer-to-peer transactions. Blockchain turns away from matters of trust that depend upon a stable center and a distinctive form, and toward notions of transparency and the consensus of code that circumvent such dependency. This alternative constitutes a computing infrastructure that invites us to inhabit a segmented, transparent, and vast transaction-encoded timeline. Precisely this effect is achieved in Beeple’s collage, as the relationship between the images, available for public viewing online, mimics the relationship between public records of sale on Blockchain. The relationship is that of a counterintuitive fragmented groupness—one specific transaction does not necessarily follow from the one before it, as each is a discrete, siloed record of one-at-a-time asset exchange. This kind of assemblage is determined by the rigid chronology of record keeping, remaining intact in a “disjunctive unity” of an immutable account of sequential purchases.

These qualities of non-differentiating boundlessness, fractured timelines, and image-dominated reality recall the key attributes of postmodernism as theorized by Fredric Jameson, in his 1980s essay “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” In the essay, the postmodern form is exemplified in the Westin Bonaventure hotel, designed by John Portman and constructed in 1976 in Los Angeles, USA. The first thing that strikes Jameson as distinctive about the building is the structure’s relationship to the world that surrounds it. Portman’s design, Jameson claims, creates a structure that does not want to be a part of the city but rather “its equivalent and its replacement or substitute.” The glass façade of the hotel reflects its surrounding, both taking on and repelling the urban setting, effectively blinding the onlooker to its form. The simultaneous vastness and invisibility of form is internalized by the structure in creating a disorienting interior via myriad architectural elements—streamers, escalators, and balconies inside the building that appear to “distract systemically and deliberately from whatever form it might be supposed to have.” Part of the disorienting effect comes from an absence of a coherent style, and an embrace of formal pastiche—an uncritical replication and amalgamation of already-existing styles. The feeling such qualities produce for the visitor is one of total immersion in the space, which removes one’s ability to attain a critical distance from the structure and account for composition, depth, or volume. For Jameson, that human inability to catch up with the speed of the mutating structures around us signals a distinctively contemporary “incapacity of our minds, at least at present, to map the great global, multinational and decentered communicational network in which we find ourselves caught as individual subjects.”

Jameson’s essay, originally a public talk given in 1982, reads today as a description of an onset of capitalist postmodernity as an aesthetic circumstance that tends to displace the subject and discourage formal thinking. Perhaps the human mind has, with time, proven its capacity to “map” the aforementioned “decentered communicational network,” and the Blockchain is the closest thing to a map that we have. The problem of the postmodern structure (if one, like Jameson, chooses to see this as a problem) is in its vast, ungraspable, decentered unyielding to the human capacity to think form. It then appears that the Blockchain-affiliated EVERYDAYS picks up where Bonaventure left off and inaugurates a transition from consumer capitalism (Portman’s hotel being riddled with boutiques and restaurants) to financial capitalism that privileges the matters of deal-making and risk-calculation.

The “great reflective glass skin” of the Bonaventure hotel resembles Beeple’s shimmering archive that reflects a series of disjointed events in its mirroring and form-concealing fashion. Existing in the context of proclaimed radical financial rupture, Beeple’s collage imagines visual space in temporal terms, its aesthetic organization echoing the decentered global technology that supports and surrounds it. A result of years-long daily practice, EVERYDAYS encodes time in pictures and enacts, to use Jameson’s language, “the transformation of reality into images, the fragmentation of time into a series of perpetual presents.” This effect, art historian Peter Osborne claims, is characteristic of the “contemporary” as a historical and theoretical concept: “A projection of unity onto the differential totality of the times of human lives,” Osborne explains, which results in a "disjunctive unity of present times." Following Jameson’s approach to the postmodern form, the temporal and formal aspects of The First 5000 Days, which internalize the Blockchain technology underpinning its participation in art trade, may be productively read as speaking the language of its time.

EVERYDAYS figures a turn away from linear narrative temporality and centralized financial institutions, which the crypto revolution targets, and gives a sense of what crypto emancipation might feel like. The popular equation of the emerging crypto sphere to the “Wild West” may not be too off, as the adrenalin-fueled chase for profit in a radically unregulated sphere of asset transfer is all too reminiscent of a gold rush: everyone for themselves. It is no surprise that the premise of stateless money exudes a staunchly libertarian or anarcho-capitalist assertions in the market’s ability to take care of itself. Thus, social relationships are no longer supported by the social contract built on mutual trust but rather determined by varied practices of opportunistic risk-taking.

In her 2017 volume Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain, Ruth Catlow addresses the matter of trust as follows: “In cryptocurrency,” Catlow writes, “trust in people and institutions is replaced by trust in the fairness of market forces and the mathematics of cryptography which prevent counterfeiting and maintain its security." Five years after their publication, these lines may not read as affirming today. The crypto sphere has time and time again proven its vulnerability to security violations as any systemic shortcoming—from weak code to a transaction loophole—can undermine the security crypto claims to provide. Amid a historic crypto market crash, it may be of use to revisit and reevaluate this morphing of trust in people into a consensus about systems. For while these uneasy aspects of crypto economy are undeniable, their infrastructural basis ought to be seen in the context of a traumatic loss of trust in fiat institutions. After all, the emergence of crypto currency shortly after the 2008 financial crisis made a strong claim for generating value while bypassing centralized institutions of (long-waning) financial credibility. For while these uneasy aspects of the crypto economy are undeniable, their infrastructural basis ought to be seen in the context of a traumatic loss of trust in fiat institutions. Afterall, the emergence of crypto currency shortly after the 2008 financial crisis made a strong claim for generating value while bypassing centralized institutions of (long-waning) financial credibility.

In crypto, the value is in part derived from the uniqueness (immutability) of the blockchain token. NFTs are an attempt to leverage the uniqueness of crypto tokens by affiliating them with entities that are produced and exist outside the Blockchain, most notably digital artworks. Through the marriage of a token and an artwork, the latter is prescribed a status of a one-of-a-kind item, its scarcity resulting in the art world (trading) value. Ironically, in the context of the 2021 sale, the Blockchain’s claim to remove trust from the transactional equation is inverted, as the matter of trust is smuggled back in via the external (non-Blockchain) institutional verification since Christie’s functions as a guarantor of the NFT’s legality and the work’s authenticator.

So, while listing the first fully digital Blockchain work to be sold by an auction house, Christie’s includes “this work is unique” in the lot's details section, alongside the work’s title, mint date, and dimensions. By blurring the distinction between the uniqueness (authenticity) of the artwork and the uniqueness (non-fungibility) of the token, Christie’s melds the processes of aesthetic judgment and investment calculation. This characteristically postmodern merging of categories is of importance since the matter of credibility lies at the core of reading EVERYDAYS as legitimizing cryptocurrency and the Blockchain infrastructure as available producers of value. Blockchain currencies are riddled with doubt and risk not only because of the absence of a stable center and the vulnerability of code but also because the concept of a new monetary medium as a viable alternative to the existing currencies has not been entertained for several centuries now.

**********

Illustrating the relationship of Beeple's work to the long-established union of art production and wealth manipulation, the second part of this essay proposes a formal consideration of EVERYDAYS alongside 18th-century trompe l'oeil prints that commemorated instances of financial catastrophies.