The pair is the ur-unit of curation, someone says to me. I take issue with this. I believe I resent all pairs, see all coupling as pathological. What kind of disease infects the eye tasked with comparison? Yet how else may love move among objects?

A pier collapses into the Hudson.

But not to speak about ruin. Not to make ruin the version that gives way to reconstruction, the abject architecture failing fully to hold the world. Not to let the Roman referent rise when Gardner titles the image, points us from the bombed-out South to the classicism the camera can make available to the eye.

What happens if we think of them as one photograph? What are the good questions to ask?

Impossible to think of them as one photograph; to elide the historical difference would be an erasure. But to reduce to historical difference is also to erase.

What happens if we think of them in overlay? America dies into itself in 1865, in 1975-1986 (sometimes a date is a range).

The images move in and out of each other.

And what is the task of the scholar? I put them together, or apart. What is the task of the poet? I put them near one another. These tasks are not the same, but they are not mutually exclusive.

*

In 1865, photojournalist Alexander Gardner assembles a monument. He compiles 100 photographs depicting the sites and sights of the Civil War. For each image, he writes a description, narrating in sometimes florid prose the tragedies and heroics of the war. The photographs are authored by a variety of embedded men, sometimes Gardner himself. Changes in camera technology meant this war could be represented in a slow version of real-time, in photographs, though only as an aftermath. Reproduced in print publications, these images circulated war’s reality to the general public, beyond the battlefield. Exposure times were too long to capture action; hence Gardner’s collection of quietly destroyed landscapes and the occasional stiffly posed group portrait.

It’s a book made of only versos, a book made mostly of blank pages. On every other page, a text or a photograph. Letterpress descriptions and albumen prints—to print might mean the press of metal type upon the page or the exposure of light-sensitized paper against a negative. There is a rhythm to all of this. The pages are heavy; the clay paper brittle. One turns, reads, turns, sees. The texts come before the images. The hand of the reader cannot be innocent, avoids touching the surface of the photographs.

The librarian tells me, I’m going to ask you to turn the pages more slowly, to be more careful with the material. I have learned the rules: no garments on the table, no pens, no folders. I have learned to walk past the guard at the front, around the corner to the lockers, and to deposit my things under the protection of a four-digit code. I have learned to leave my personal writing utensils in my purse, and instead to take a branded, sharpened pencil from the cup at the circulation desk. I have learned to ask for my items with minimal embarrassment, which is not to say none. What is the task of the body made present? To access, to move through space. I have learned to be in the room, but it doesn’t stop the blushing. The librarian walks away. But what is the material?

*

In 1975, Bronx-born artist Alvin Baltrop begins photographing the life of New York City’s West Side Piers. Abandoned at the border of a deindustrializing city in financial crisis, the piers invite cruising and sunbathing, voyeurism and encounter. For those with nowhere to go, the piers can be made home. Manhattan has zoned gay culture to its margins.

Baltrop is several years out of the Navy. He drives a cab until he drives a moving van. Sometimes he sleeps in the back of his van, living for days at a time at the piers. This might be read as a species of devotion, a practice of intimacy between artist and subject matter. I’m not sure I want to reduce Baltrop to mere creative eccentricity, nor do I read his eye as purely indexical. But then what draws me to this work, aside from devotion?

I make an appointment at Baltrop’s gallery. En route, walking down 5th Avenue past the Met, a man walks several yards behind me, carrying a speaker playing Rihanna’s “Love on the Brain” loudly. The song ends and our paths diverge. I’m eager to see the photographs; Baltrop means something to me I still don’t understand. I wonder, as always, about the fetishization of contact. At the gallery, much of his surviving oeuvre—some 300 images—is arranged by series in archival boxes. The process of looking is a process of handling: laying things flat, slipping prints from their sleeves, doing noisy battle with plastic taped shut.

Baltrop constructs a makeshift harness and shoots suspended from the warehouse rafters. The figures in the photographs seem incidental to the architecture. They move through rooms, perch on piles of abandoned timber. Many wear nothing but socks or shoes.

*

The day after my Baltrop visit, I walk along the Hudson from Canal into Chelsea. I have wandered this strip of river so many times, with friends and alone, watching the water bounce shine onto joggers and bicyclists moving along the city’s edge.

I am with my friend Cam, going from gallery to gallery. Now that I live two hours away, we steal time and there’s never enough. There are those who bind us to ourselves; our cities constituted by conversation. I have Baltrop in my eyes: the portraits, the feats of chiaroscuro, the warehouse buildings cum urban landscapes. Cam hasn’t seen the photographs, but he has heard me thinking through them for months. One night we stood forever watching white golf balls fly into an illuminated cage at the Chelsea Piers, hearing the sound of the swing and the hit. But I always feel the prior versions, sense structure’s release into something else.

We pull open the heavy doors, move through the rooms, stand side by side in front of the images. When we’ve seen enough, we end up on the High Line. An endless row of people in puffy coats and sunglasses occupies the wooden loungers. We sit on a bench facing them, the river and sun at our backs.

*

Invented in 1850, the albumen print became popular because it produced a rich sharp image. The process involves coating a sheet of paper with albumen (egg white), making the paper’s surface glossy and smooth. It is then coated in a solution of silver nitrate. The albumen and the silver nitrate form light-sensitive silver salts on the paper. When a glass negative is placed directly on the paper and exposed to light, it forms an image on the paper.

*

You don’t belong here, says the photograph. What do you know about me?

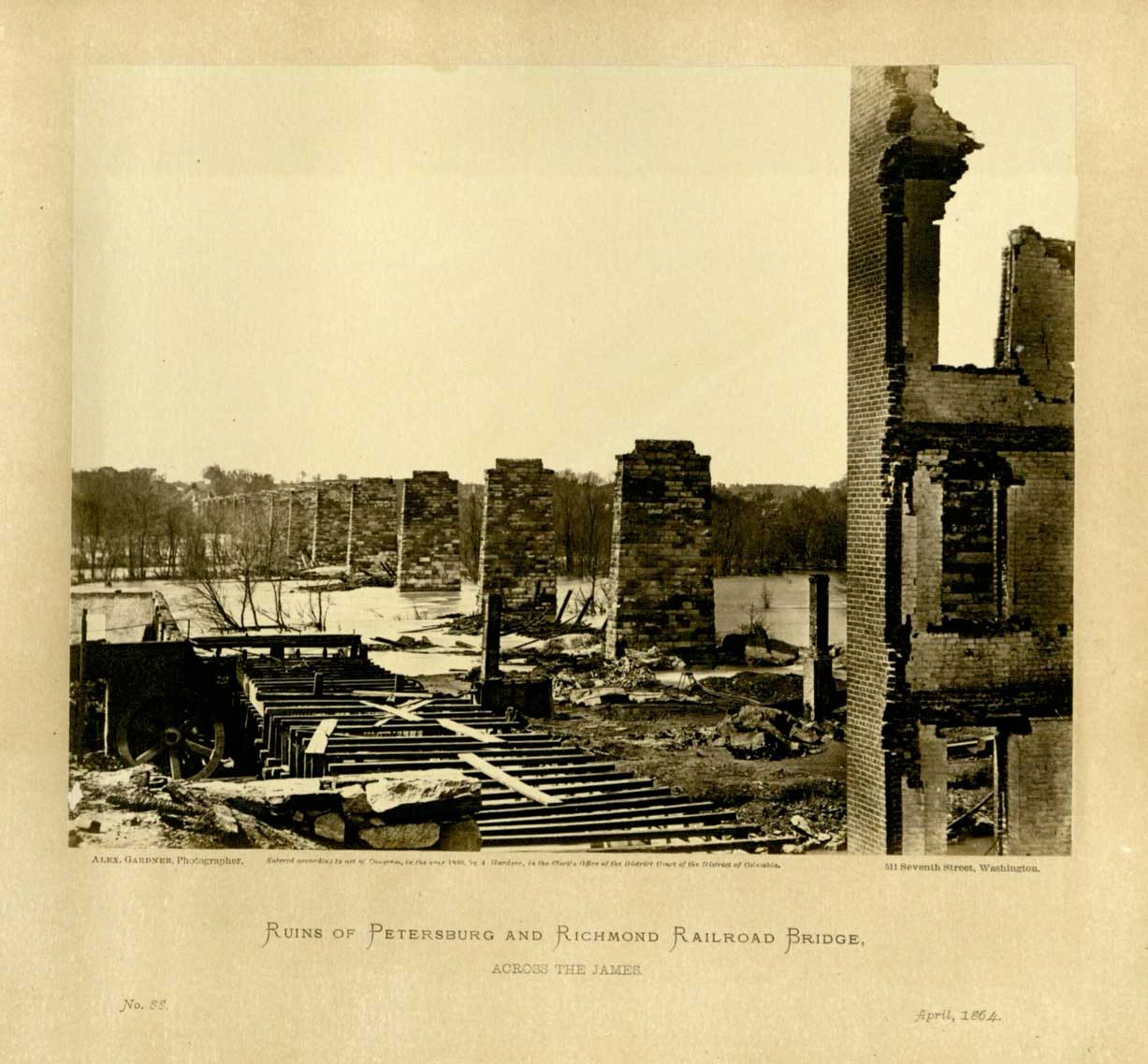

Look at where the warehouse touches the water. At its lowest point of collapse, a finger of siding juts out, one corner immersed in the river. The structure was built of wood, and rested on sixteen large stone piers. It had two passage-ways, one along the top for the cars, and one beneath the railroad track, for carriages. This view was taken from the Richmond side of the river, where are the ruins of a large paper mill.

The advantage of the albumen process is its shine. The egg whites dry to form a smooth layer. The image forms suspended in the coating. Albumen does yellow with time, however; when I turn the pages, I see a vague warm wash. Yet the photographs are still sharp, the teeth of the exploded wall distinct.

What is the material? Light hits the plate. The paper touches the glass. Albumen and silver nitrate react. A collapsing building enters the water. A brick wall alludes to ancient history. Architecture elucidates an elegant failure. The photograph holds it together, mostly. I hold it in my hand. I try not to touch the surface. I look at the image. I try not to go under, to fall into form, perform the kiss or the hand in hand the pairing of light and paper prepares.

*

[At what point does the experimental become merely sloppy?]

One part of looking might be looking away.

Baltrop dies at 55, in 2004. Few but his friends see the Piers photographs before then.

Gardner prints some 200 copies of his two-volume leather-bound masterpiece. Almost no one can afford it, each heavy page edged in gilt.

When looking from one to the other, we must ask what is in practice, what is at stake. Does love move among objects? Can a pair be more than two, less than one? Does the body have to confront the object? And what to do with the violence?

*

A new structure has been built on the piers since this photograph was made, and the trains now cross regularly. Many of the ruins along the river side have been removed. Handsome buildings are in progress of erection, and the cities of Richmond and Manchester are resuming their bustle of trade and improvement.

Gardner makes monumentality available. The country’s landscape conceals the bodies, but the ruined buildings are ragged with memory. A newness rises vertically now, when the war needs covering over. Structures and progress become synonymous. Reconstruction requires repression. Gardner shows the shattering of the self: make images, anchor them with words. Erect something. Cross the bridge.

Who would take this book off the shelf?

After the 2015 Charleston church shooting, a Confederate monument in Baltimore is taken down. In news articles about the removal, the phrase under cover of darkness circulates wildly. The threat of protests and counter-protests makes darkness the prerequisite for action. Images of this event nonetheless proliferate.

People sometimes die at the piers. Desire conditioned by structural violence does not a perfect utopia make, though we might call it a space on the side of the road. Several photographs in the boxes show bodies in bags, a drowned corpse surrounded by cops. In another set, a pier is on fire, a group of firemen gathered in a warehouse. Once the AIDS epidemic takes hold, another kind of death hovers. In 1986, Reaganomics in effect, the piers are destroyed.

*

There’s sun on the water. Weeks pass in writing this essay. I’m being trained, being trained up. The pair is the ur-unit of curation. But I resist. I train my eye but tend to trail off. The edges are charred, worn, one corner is creased. A brown stain, maybe water, floats over the buildings in the background. Several thin black lines, maybe pen, index a gestural accident where the failing warehouse bends sharply downward.

It is April on the page. The photograph as aftermath is also coeval. How many times have we met since then?

The image says horizon, says perspectival trick. I want to complicate this love.

I put them near one another, not knowing what I’m doing. I can’t get my point across.

But not to speak about ruin. Here’s the difference: Gardner wants the lasting image, while Baltrop wants only this—light, shadow, bodies moving in and out, briefly beside and sometimes apart. Is that fair to say? I want them both, differently, want the rise of the argument—this is over, this is history, here’s the future—and the fall of encounter, beloved chance to conceive of a future that could be otherwise, and in this moment, already is. I put on my scholar hat, put the boxes back in order.

We descend from the High Line near the new Whitney, ship of a building, all silver and glass.

I hand my notes to the security guard, let her rifle through to check for contraband. The figures seem incidental to the architecture. Love moves among objects.

I put them together, or apart.