When is an artwork just an artwork?

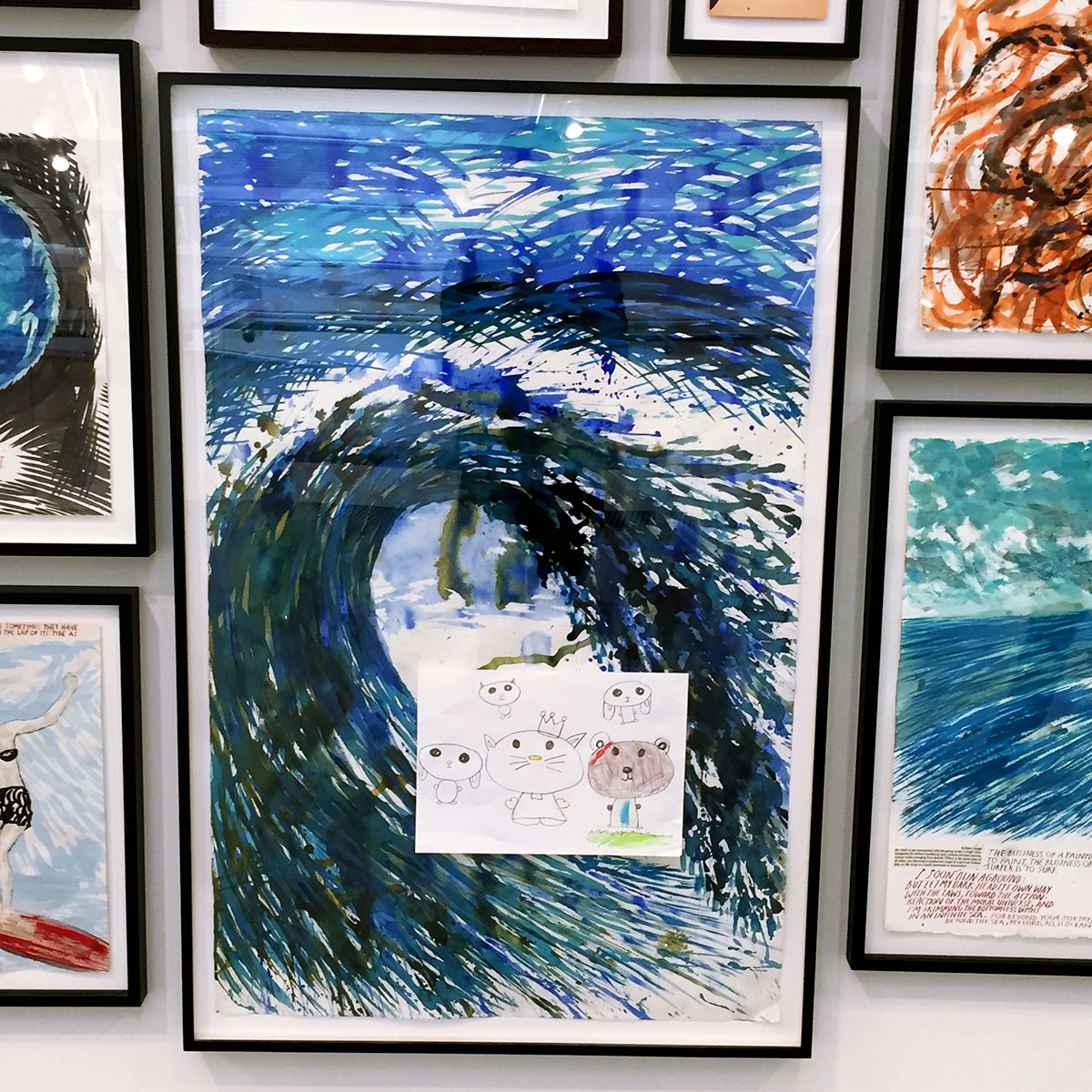

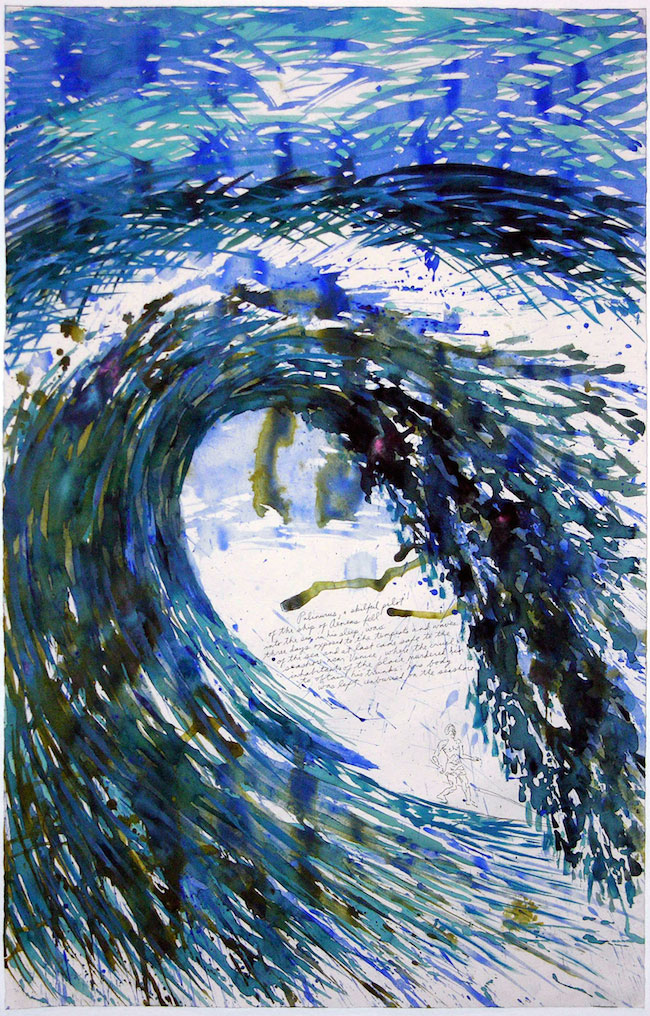

A framed work on paper hangs in a salon-style installation. Its subject and style—a single wave rendered through forceful, overlapping lines and bordered by a crosshatched sky—are recognizable as hallmarks of American artist Raymond Pettibon’s oeuvre. Presumably an artwork. But the identification is not so easy: in the bottom half of the image, another work on paper is taped to the glass—a drawing of cartoonish animals, floating on a blank ground. Still just an artwork?

In this documentary photograph, there are no visual cues to indicate whether the overlaid image is a component of the original work, an intentional intervention, or a guerrilla addition. The context outside of this image serves to increase its legibility; the salon-hang of Pettibon's works on paper was installed alongside 17 other groupings of contemporary artists’ pieces in the exhibition Love Story - Works from Erling Kagge’s Collection at the Astrup Fearnley Museum (Oslo, Norway) from May 22 through September 27, 2015. The curatorial statement—penned by the curatorial team of the museum’s director, Gunnar B. Kvaran, and curator, Therese Möllenhoff, with Kagge—informed viewers that the exhibited artworks are part of Kagge’s “remarkably well-composed” collection, which he has assembled with “unusual insight and personal judgment.” Extended wall labels in the galleries introduced each artist’s work by providing basic details about his or her practice and interests. In the case of the Pettibon presentation, the informational label that listed captions for each drawing also included an asterisked note for two of the displayed artworks, No Title (Palinurus, a skillful) (1999), seen here, and No Title (I was proposed) (1987), not pictured: “Attached children’s drawing from Erling Kagge´s home.” As an explanation of the incongruity that marked the work on view, this succinct statement raises more questions than it answers, but together with the other elements of the exhibition’s framing, it effectively hints at the key factors and players that come to bear on this artwork’s status: collector, curator, and institution.

In the case of Love Story, the collector’s role is paramount; as the exhibition language indicates, the show’s chief purpose was to showcase how Kagge’s distinctive vision guides his acquisitions. Through this lens, each included artwork was presented not just as an aesthetic object, but also as evidence of his unique criteria for collecting. Kagge further defines the nature of his choices in an interview with Kvaran: “collecting is kind of an autobiographical thing to do. I find it very personal.” According to this formulation, each artwork from his collection carries traces of Kagge’s hand alongside that of the artist; while the artist crafts the work physically and conceptually, the collector adds to it the context of his unique background, preferences, and associations.

This way of thinking about a collector’s role invites speculation on the boundaries of such an individual’s influence; for example, does this logic make it appropriate for the collector to change the actual appearance of an artwork by attaching a child’s drawing? After inquiring with a museum host to learn more about the element added to, I ascertained that the child’s artwork was left on the frame based on Kagge’s desire to display the work in the same manner as he does in his home. In line with Kagge’s interpretation of collecting, this treatment of the collection object is concretely autobiographical, as it incorporates a piece of the collector’s family and home life. But it also obscures distinguishing elements of the artwork’s composition; beneath the child’s drawing lies a paragraph of cursive text and the outlined figure of a surfer. Given that the combination of text and image plays a central role in both Pettibon’s practice and art criticism about his work (including the exhibition’s audio guide segment that provides an interpretation of the artist’s works), this particular addition could be said to highlight the collector’s hand at the cost of the artist’s. While this stance might seem obviously sound when applied to an artwork qua artwork, it has a less definitive relevance to an artwork qua collector’s possession. Since this latter categorization of art is defined by a relationship to its owner, and perhaps even by the enthusiasm fueling this relation, is it reasonable to view an additive gesture like Kagge’s (and his daughter’s) instead as an example of collection maintenance par excellence—an act of gifting that increases the work’s personal meaning and value?

Here, again, the exhibition framing seems to respond affirmatively—the show is titled Love Story, after all. In foregrounding the collector’s passion for his artworks, the curators—the next layer of influence on the artwork—encouraged viewers to regard all that was on display as objects of affection and endorsed the belief that this emotional attachment suffices as a guiding logic for collecting. This curatorial premise carries with it a set of implications that similarly can be read from multiple perspectives; while on the one hand, such an approach gives a glimpse into the subjective reasoning that guides many art acquisitions and displays (and is often covered over through scholarly justification), on the other, it spotlights an image of art as something to be lusted after (rather than respected as an important cultural expression). However, there is a difference of responsibility when confronting these concerns as a curator rather than as a collector; the role of the curator is inextricably linked to the public, whereas the collector’s interests are inherently private. In the case of the Pettibon installation, regardless of the ethics of Kagge’s artistic addition and request, it fell upon the curators to determine how to address the situation and explain it to visitors.

While the information on the label denoted that the original work was altered and conversations with the museum hosts could further clarify the circumstances of this change (if visitors took the initiative to ask questions), the fact remains that Pettibon’s drawings looked different than usual in this installation. According to a museum representative, this was not an issue for the artist, since Kagge consulted with Pettibon (through his gallery) about the decision to keep the child’s artwork on view. Yet, notably, this fact was not made explicit in the exhibition materials. Instead, Kvaran’s curatorial essay implies that such clarifications are not required, since, in his analysis, the artist does not possess sole authorship of the installation: “we can say that the collector is a creator, whose discovery, selection and arrangements of works is itself a work of art.” With this, the curator asserts that the act of collecting should be seen as an artistic expression in and of itself and thereby creates space to consider Kagge’s addition to the Pettibon frame as an extension of the collector’s creative practice—an act of art making. This line of thinking raises further interpretive issues; does this curatorial position necessarily exclude the possibility of a clear visual delineation between the artist’s original work and the collector’s personalization of it (which could be achieved by something as simple as printing a thumbnail image of the unaltered Pettibon works on the wall label)?

The curatorial premise’s emphasis on the collector’s agency demonstrates an approach that does not often find voice in museum settings, but it is one that did not seem out of place in the context of Astrup Fearnley. As a private museum founded by descendants of the Fearnley shipping family and housing the collection of Hans Rasmus Astrup, the institution has a clear affinity with and empathy for the perspective of an individual collector. However, Love Story was the first instance of an exhibition at the museum that featured an outside private collection; its staging could thus suggest that the museum values Kagge’s collection above others, that this moment was particularly ripe for examining the works he possesses, or that there existed underlying, unspoken motives for giving Kagge a platform (or some combination of these and other reasons). Regardless of the causes, the outcome of making an otherwise inaccessible collection public is positive for museum visitors—at least in the sense of viewing potential. But a variation on the questions that apply to the roles of the curator and the collector are pressing with regard to the museum: Is it worthwhile for a museum (public or private) to bring a private collection into the open on its own terms, with minimal interpretive attempts to make it and its associated politics more legible and transparent to members of the public? And moreover, how do the stakes and responsibilities change when a private institution showcases an external private collection alongside its own?

My intention is not to make a definitive argument for what should be considered best practices for a collector, curator, or museum. Instead, in outlining the impact that each one of these players has on the artwork, my aim is to point up the reality that what visitors encounter in a museum is rarely, if ever, just an artwork, as conceived and created by an artist. After passing through the hands of each of these three stakeholders (among others), an artwork is more accurately defined as an embodiment of a network of relationships, interests, and intentions that extends far beyond the artist’s initial vision. In this light, the Pettibon installation in Love Story had the distinct virtue of authenticity; in making visible the otherwise unseen factors that surround and inform an artwork, it challenged viewers to negotiate and reconcile the gap between the isolated instance of these artworks’ display and the set of interconnections that gave rise to their presentation.