I. Abstraction

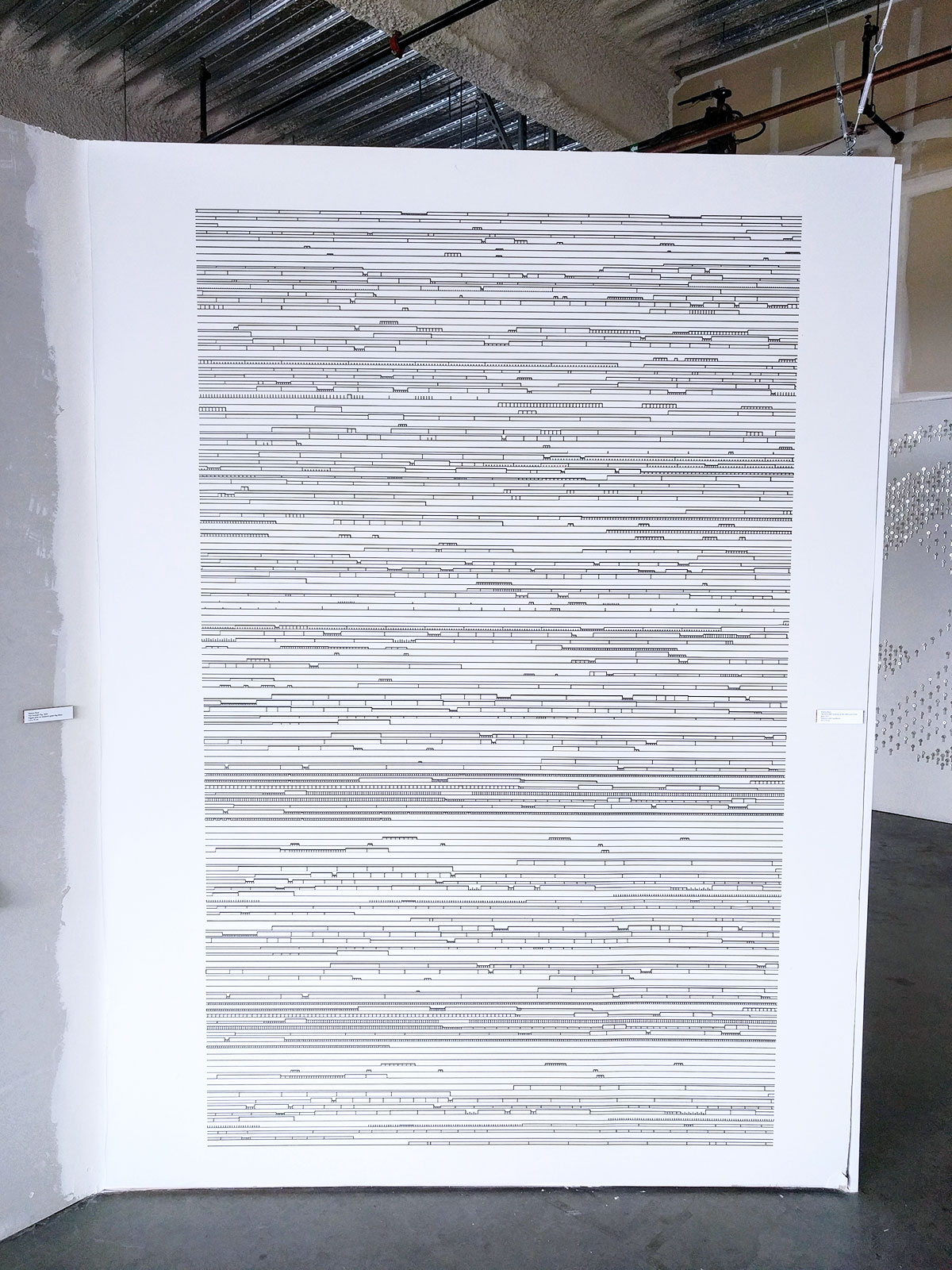

Bureaucracy is an easy target. It’s the product of the nation-state as leviathan wielding power over everyday life. It’s the law rendered inscrutable and capricious tormenting Kafka’s hapless Joseph K. to the point of madness then death. It’s cumbersome and corrupt, rife with inefficiency and disregard for basic human needs. Patricia Reed’s The Uninscribed Taxonomy of that Which You’ve Been Given (2010, on display at the Museum of Capitalism, Oakland, California, summer 2017) offers a critique of bureaucracy along these well-trodden lines. Examining the problem of citizenship and immigration on a global scale, Reed’s artwork layers blank citizenship forms from all UN recognized nation-states to produce an imposing collage of dashed lines and clustered squares. Using documents emptied of language and instruction, the artist creates an abstract picture of an already abstract bureaucratic process. This seamless equivalence between artistic and political abstraction, however, should give one pause as it raises difficult questions about the implications of Reed’s critique and the role of bureaucracy, institutions, and the state in everyday life.

When reduced to lines and geometric shapes, the citizenship forms that comprise Uninscribed Taxonomy are rendered unintelligible and unusable—or put differently, they become emblematic of an equally obtrusive, arguably broken system. By relishing in the visual and verbal pun between cumbersome aesthetic and official forms, the artwork foregrounds the shortcomings of a citizenship model tied to the nation-state. It’s a model, the artwork’s rigid boxes and horizontal lines suggest, that classifies people according to nationality, gender, age, or identification number. A model, in other words, that reduces an individual, desiring and emotive, to little more than an abstraction, a statistic or thing. Invoking abstraction in this way underscores a dire contradiction: as the movement of people reduced to things is policed by immigration agents and constrained by bureaucracies, the thing-as-commodity, also rendered abstract through exchange value, moves freely between borders in a global economy. The towering scale of Uninscribed Taxonomy illustrates this paradox. Well over six feet, the collage resembles a barrier or wall, recalling the countless walls and fences erected across Europe in recent years to keep migrants and refugees out and nation-states intact. The artwork of course also brings to mind Donald Trump’s long vaunted border wall between the U.S. and Mexico. “A nation without borders,” he’s quick to remind a horrified and enthralled public, “is not a nation.”

Reed’s critique of closed borders with their appeal to the nation-state and nationalism, as well as of immigration processes that too-often serve as a further barrier to mobility and a means of dehumanizing vast populations, is certainty well-founded. However, by rendering citizenship documents indecipherable, even defunct, and casting the legal system as an insurmountable obstacle, the artwork discounts the promise and potential of documentation, and the path to citizenship it can provide.

To grasp this other side of bureaucratic and institutional frameworks, one should look no further than the Trump administration’s recent vow to rescind DACA, and to the positive impact that legal status and permanent residency has on the lives of countless immigrants otherwise forced to work illegally or take jobs well below their level of qualification, to evade police and remain vulnerable to exploitation and violence. Making a case for unfettered mobility, for dismantling cumbersome bureaucracy with its byzantine paths toward citizenship, and for the dissolution of state institutions replete with concrete protections falls considerably short of addressing these and other problems facing immigrants across the U.S.

More to the point, when cast in these terms, Reed’s anti-institutional critique, shared by artists and intellectuals across the political left, seems uncomfortably compatible with the alt-right’s goal of deconstructing the administrative state. Of course, crucial differences remain. For conservatives as well as the alt-right, hollowing out governmental institutions by slashing budgets and leaving vacant countless positions has the dual effect of reducing the efficiency of regulatory agencies and easing rules for capital gains all the while redistributing federal resources toward increased military and police presence. While Uninscribed Taxonomy lays bare this very contradiction between unrestricted flows of capital and the policing of populations, it also suggests the solution to allow people the fluidity granted to capital in a global economy. Doing so hardly solves the problem. At worst, it sets the groundwork for a dangerous equivalence between people and commodities, which casts the problem of immigration, of statelessness, as one that can be resolved through the logic of capital.

To underscore this compatibility between anti-statist positions on the left and the right is not to imply a false equivalence or to suggest that artists on the left share latent sympathies with ideologues on the right. This parallel is instead useful for demonstrating the way in which anti-institutional and anti-bureaucratic critique, a stalwart of the left since the 1960s, has been enthusiastically, even profitably, adopted by the right as a means to sow mistrust in the government (or governmentality, as Foucault would put it) and justify the defunding of public institutions and social welfare programs, along with the deregulation of industry. I’m certainly not the first to reach such a conclusion and yet the problem remains. How does contemporary art, especially politically engaged art, and leftist politics move beyond an already co-opted critique of capitalism and the nation-state? How do artists and intellectuals contend with the worst refugee crisis since World War II; how do they address resurgent nationalism and totalitarianism without overcorrecting and abandoning the welfare state as swiftly as one would the fascist state, totalitarian state, or administrative state? The hazard of doing so, Hannah Arendt is quick to underscore in The Origins of Totalitarianism, is that without the protections of citizenship, without entry into the law, so to speak, with its tangle of documents and institutional barriers, people risk “being thrown back…on their natural givenness, on mere differentiation.” Or put in terms specific to our contemporary moment, they risk being thrown back into global circuits of migration and precarity; they risk precisely the kind of dehumanization that Uninscribed Taxonomy critiques.

II. Everyday Life

We can, I think, begin to contend with these problems of citizenship, bureaucracy, and the state by looking more closely at the forms that comprise Reed’s work. In the photograph of my mother’s kitchen table— taken the week after I first saw Uninscribed Taxonomy at the Museum of Capitalism in Oakland—citizenship forms and immigration documents are strewn along the far end of the table. The documents, completed and ready to be mailed, are slightly obscured by towering roses picked from my mother’s garden. Next to envelopes and a small vase are roasted and peeled peppers, crumpled napkins, and a stapler that would be otherwise inconspicuous were it not for the small stack of hundred dollar bills upon which it rests. This perhaps odd table-top arrangement needs some explaining. For over fifteen years my mother has worked with immigrants in Sacramento’s Russian and East European communities. Fluent in several languages and having learned from my family’s own struggle to gain permanent residency and then U.S. citizenship in the early 2000s, she now helps others apply for citizenship, secure political asylum, and obtain work visas. For as long as I can remember, our home has been her office and her work more or less unofficial. This is all to say that for my family these documents and the struggles, triumphs, and experiences to which they are testament have long since been familiar and commonplace, imbedded in our everyday life in a manner as ordinary as preparing a meal or receiving payment for one’s work.

What is significant about the everyday here, is not the way in which this category normalizes the process of immigration, or makes the inefficiencies of bureaucracy routine and therefore more palatable. Instead, and following Henry Lefebvre, I want to think about the photograph and the forms on the table as representations of everyday life replete with the concrete needs and desires, frustration and fulfillment notably absent from Reed’s work. “The human world,” writes Lefebvre,

is not defined simply by the historical, by culture, by totality of society as a whole, or by ideological and political super-structures. It is defined by this intermediate and mediating level: everyday life. In it, the most concrete of dialectical movements can be observed: need and desire, pleasure and absence of pleasure, satisfaction and privation (or frustration), fulfilments and empty spaces, work and non-work.

Of course, to suggest that what is missing from Uninscribed Taxonomy is the potential for fulfilling vital needs, seems less like criticism than a reiteration of the artist’s central point—that the citizenship form much like the model of citizenship tied to the nation-state hinders mobility and thus fails to grant access to a life where even basic needs are met. In the photograph of my mother’s kitchen table, however, the form itself represents a locus of desire, a site of potential fulfillment in its very capacity to be “filled,” completed, and submitted in a manner that is disallowed in Reed’s depiction of the form as a barrier rendered always already unintelligible and unusable. And more to the point, the potential fulfillment of needs and desires these documents make possible are evident right there in stuff that clutters the table—from the bowls to the paperwork, to the idea of a kitchen, a house, a home, stability, safety, and work.

For my family, like many immigrant families who have yearned for documentation for access into the law and the protections it grants, bureaucratic institutions represent not only ideologically laden abstractions but also concrete systems and negotiable processes. Casting bureaucracy in this more sympathetic light is certainly not to excuse its extensive failures or to suggest that one should be content with immigration policies as they stand—to say that immigration in the United States or Europe is far from perfect, is a gross understatement. Rather, it’s to suggest that it’s not enough to simply underscore the flaws in immigration and citizenship processes without offering something else in their place (doing so echoes the swiftness with which House Republicans and the Trump Administration sought to repeal the Affordable Care Act without proposing a viable alternative and with little regard for millions left without healthcare).

To reiterate, bureaucracy is an easy target and its critique pervasive. Even in its most mundane iteration, delayed trains and busses, long lines and lost forms yield immediate frustrations and real consequences. The solution, however, is not to do away with infrastructure, to criticize its inefficiency and leave it in disrepair, to let it “implode,” as is Trump’s tactic for handling the shortcomings of the ACA. Instead, what is considerably more difficult and yet necessary for artists, activists, and critics on the left is to propose alternatives, to offer concrete solutions that contend with the embeddedness of bureaucracy and the state in everyday life.